12. My Aunts Doris and Sheila

Marjorie 1892-1993 101 years; Doris 1895-1981 86 years; Sheila 1902-2008 106 years.

My grandparents Lucie and Willie had five children (including Desmond who died aged two). The eldest, Marjorie, married Edmund Mitchell in 1914 and the youngest, Dermot, entered the business in 1927. This chapter is about my Aunts Doris and Sheila, known as Auntie Do and Auntie She, whose lives covered almost the entire 20th century, and it shows the quiet contribution made by these two wonderful ladies.

My story starts in Glenageary in the spring of 2000. As we relaxed over a glass of sherry, reflecting on another pleasant hour of taped conversation, my ninetyseven- year-old Aunt Sheila said that she had had a wonderful life. We had spoken of her thirty-two years as secretary to Lady Meath in Kilruddery, her years in the Irish Girl Guides, from its inception to Commissionership; of the carrying of the tricolour around Wembley Stadium in the First World Girl Guide Conference and a visit to Buckingham Palace; of her days travelling Ireland for the Irish Countrywomen’s Association and the teaching of handcrafts, judging at country shows and staying in the most humble of abodes; of her love of the Church and her term as Chairman of the Friends of St Patrick’s Cathedral; of her shared loved of the garden with her sister Doris and above all the happiness of seeing all her nephews and nieces and their offspring turning out so well.

I remember I wanted a bicycle, I suppose it was about 1910 or so, and in those days the family didn’t give you a bicycle, you either tried to earn a few pence weeding the garden or doing odd jobs, or you collected your pocket money and Christmas presents. We did everything on bicycles—we went to church, to our friends, to shopping and on picnics in the countryside. It was wonderful in those days.

My grandmother came to dinner with us on Christmas night. She always gave us a five shilling coin. You felt you were a millionaire with that. Then the day came when you got a little half sovereign. I think of nowadays when I hear the young saying: Oh yes, they have this, that and the other thing—they don’t know what it is to save. I had saved up towards the bicycle and Uncle

Marjorie, Sheila and Doris in 1904 (Photo: William Lawrence)

FINDLATERS

Charlie [the engineer, who died on the Somme] was asked to see what he could do— he may still have owned the bicycle shop in Dawson Street. Anyway, I was thrilled. It was a Raleigh bicycle, it was a real bicycle! I had it until the last war, the Second World War, and eventually the gardener got it for his family.

Once in a blue moon, Uncle Adam would come around in his car—or was it Uncle Charlie?—and take us out for a gander up the road. It was one of those original cars, say 1910 style. He wore a soft cap back to front. If you live long enough you live history! But life has changed so much since then.

Aunt Sheila remembered that the business was never far from the family’s thoughts:

Findlater’s in those days gave a dinner for the staff in the middle of the day in O’Connell Street, not the branches—there was a big staff dining room for the staff. I remember when I was little you’d be left in there while mother went out to do a bit of shopping and one of the staff would look after us. And then there was the director’s dining room. I vaguely remember the staff billiard room—they would have their dinner and then there would be a quarter of an hour or half an hour, and we would hear the billiards balls clacking.

I remember how one time the Howth peninsula was more or less cut off and my father went in a boat from Ringsend with sacks of flour for Howth—perhaps that was 1922.

I used to go with my father on Saturday and we’d go either out to Howth to visit the St Lawrence Hotel and the shop or alternatively we’d go to Bray. I’m sure I visited the Royal Hotel in either Bray or Howth, I think we used to own both. We’d get one of the cabs that waited outside Findlater’s in those days, a horse-drawn cab. And my father would say: ‘Westland Row, and take your time’—it always puzzled me. He surely knew the cabs weren’t going to go at fifty miles an hour! And so we trotted down to Westland Row and we’d get the train down to Bray, or we’d go to Amiens Street to go to Howth. But it struck me one day that he needn’t have said: ‘And take your time!’

Transferring to the Church of Ireland

My father had been brought up a Presbyterian, but mother was the stronger Christian and a member of the Church of Ireland. Thus the next generation were brought up Church of Ireland. My father was a twice a year Christian —he went to church on Christmas Day and Easter Sunday—–he was a renegade! Originally we went to Booterstown—that’s the church on Merrion Avenue. We were then living in Melville, Avoca Avenue, and in those days we hadn’t cars. You just walked to church. And then I think it was when my sister Marjorie got engaged to Edmund Mitchell that she persuaded mother to go to All Saints in Carysfort Avenue, Blackrock where Edmund sang in the choir and could play the organ if the organist was away. Doris and myself sang in the choir and we held the church féte in Glensavage for some twenty-five years. We were very good friends with Harry Dobbs, the vicar, and his wife Katie.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Edmund Mitchell, who died in 1945, was fondly remembered in the parish, as Canon Dobbs wrote in the Anglican newspaper the Church Gazette:

From the time he was a choir boy, fifty years or more ago, until the day he lay down to die, Edmund Mitchell served our Church with an almost unparalleled fidelity. Others of its friends might come and go, might serve it for a while and then fall away and walk no more with us, but Edmund Mitchell never failed in his allegiance and, true as steel, stayed true until God touched him and he died. The quietest, most modest, most self-effacing of men, he brought a pure and peaceful wisdom to our Councils, which soothed acerbities, and a quaint humour all his own which dispelled in smiles and laughter what might have been the beginnings of one of those petty storms which rage from time to time in every Parish and so made everyone happy and friends again. In return the Parish gave him everything it had to give and heaped its little honours on him until it had given all.

He was a vigilant guardian of our Church traditions, such as they are and in many ways helped to create them. Attempts to lower its standards, to change its distinctive note, its gentle but effective traditions, moved him at once to protest and found him standing foursquare for the simple dignities that have marked its ceremonial from its Foundation. A sensitive musician, an artist to his fingertips, he was the most faithful of choristers and was seldom absent from his place. Many of our older folk have told us that one of their chiefest pleasures on Christmas Day was his singing of ‘Nazareth’ before the Eucharist, but his singing at all times was a delight. And now, this good, kind, greatly loved man, this loyal Churchman, this steadfast Christian gentleman is gone from us and another loneliness, another deep sadness has fallen upon a Church that has lost many friends in recent years. But he will be remembered always with affection and gratitude, and with thankfulness that we had with us for so many years, so good and true and wise a man. May light perpetual shine upon him.1

This tribute was written by Canon Dobbs*, himself a great local character who later in life propelled himself about his parish in his motorised wheelchair, even to the top of Newtownpark Avenue where we lived. His comment on the parish fête in Doris and Sheila’s garden in the summer of 1944 gives a flavour of the Anglican religious spirit of the day:

We cannot but think they could have pleased God. We think our Fêtes must please Him. He liked Parties Himself, and a Parish Party that brings people together in friendly social intercourse and mixes them all up and makes them rub shoulders with each other and play and talk and laugh together, must delight Him. Anyway, He has always blessed it, and never more than this year. What can we say to these things except to thank Him for having put into so many hearts such good desires, and for giving them grace in such generous measure to bring their desires to such marvellous effect, and not least for having put it into the hearts of the Misses Findlater to give us the use of their glorious garden.

* Rector of All Saints, Carysfort Avenue, Blackrock, 1914 to 1949; Treasurer St Patrick’s Cathedral 1942 to 1949 and Precentor of the Cathedral 1949 to 1952. Born in 1876 in Castlecomer, the youngest of 10; died 1961. Married to Kate (Kathleen), a grand-daughter of the Earl of Rosse. He used to say: ‘Kate has the blue blood and I have the brains.’

FINDLATERS

He returned to the theme after the 1946 fête, which was not blessed with such good weather, and yet—

it was a huge success. It rained of course, the skies wept copiously, but in spite of the rain, in spite of Moiseiwitsch, Leopardstown, and another Fête not far away, Glensavage was so filled with friends that we laughed and sang as cheerfully as if it had been the loveliest day of the year. For could there be anything lovelier than the loyalty, kindness and goodwill which brought as many, if not more, people than ever on such a miserable day to help us along and to spend so gaily that the receipts were actually twenty-five to thirty pounds above the average. And not a grumble, nor a melancholy face to be heard or seen anywhere. The gardens were sopping, of course, but so enchanting that one stranger was overheard to say to another that it wouldn’t have been a bit surprising to meet Adam and Eve there. They might have added ‘or a more August Person than either’ for where kindness and goodness and love are, there God is also. No one likes to be thanked on these occasions, many people dislike thanks intensely but we must acknowledge gratefully all that so many people did to avert disaster and to secure success—to the helpers who worked without fuss or plaint; to Mr. Vere-Westrops, who did everything and forgot nothing; to the Miss Findlaters, who took the spoiling of their house by muddy boots and dripping clothes as if they liked it; to the people who spent their precious petrol as though it were water bringing invalids and others to and from their trams or homes; to the friends who lent and transported chairs, and to the kind people who unable to come remembered us; to them all, whether they like it or want it or not, our most grateful thanks.

After Canon Dobbs retired Doris and Sheila transferred their allegiance to St Patrick’s Cathedral. Sheila continues her story:

I worked with five Deans in St Patrick’s Cathedral. I was nominated by the Cathedral Chapter to the newly formed Council of the Friends of St Patrick’s Cathedral in 1948 and served continuously until 1978 when I was appointed Chairman. I remained Chairman until 1982. My sister Doris also served on the Council, from 1959 to 1966. She was very active in the Cathedral Flower Guild, doing large floral arrangements for important services. I enjoyed needlework and repairing the embroidery on the clerical stoles and making up new stoles. I also made cloaks for the choirboys.

Naturally Canon Dobbs would get his grocery requirements in Findlater’s in Blackrock, though on one occasion the ebullient manager Billy Vaughan (whom we have last seen rolling oranges and apples to the Sherwood Foresters in 1916) let him down. The Canon discreetly whispered his order over the mahogany liquor counter at the back of the shop, and was embarrassed to hear Billy repeating the order in his deep booming voice: ‘A bottle of best Jameson for the Canon.’

Alexandra College

My aunts went to Alexandra College, then in Earlsfort Terrace. Founded in 1866, it had strong Church of Ireland links but was open to all religions. It took girls up to university entrance and provided them with a good broad education. In

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

1897 the Head Mistress, Miss White, proposed the formation of a bond of union between the College and her past students and the Alexandra College Guild was formed.2 It was suggested that the Guild should have some definite objective to justify its existence and thus was born the Alexandra Guild Tenements Company Limited. It was started with a capital of £1,000 [€130,000] consisting of 200 shares of £5 each. It claimed to be the first public company in Great Britain and Ireland started by and managed entirely by women.

The object was to buy rundown tenement buildings, do the necessary repairs, charge rents in the range of 1s to 3s 6d a week and give the investors a return of 2½ per cent. The rent was strictly enforced. It gave the girls a great insight into the social deprivation in certain areas of the city and taught them to be caring.

Doris and Sheila were too young to be in at the inception of the Guild. Nevertheless Sheila recalls that it was the senior class in the College who collected the rents on Monday mornings and that Doris would always bring a bunch of flowers. Later, they were joint Treasurers of the Alexandra Guild for several years and held various fundraising events in their garden in Blackrock. When gas was rationed they used to bring cooked meals to some of the needy families, quite tasty meals. The tenants were suspicious of strange food and on one famous occasion one asked: ‘What’s this?’ and the woman next to her replied: ‘Don’t be silly, this is educated food!’ and that became the aunts’ stock phrase for a good dish.

The houses chosen were well built, but they were in an almost indescribable state of dirt and neglect. The sanitary accommodation was of the very worst description, and quite inadequate; a large outlay was therefore necessary to put them into proper sanitary condition. The roofs were also dilapidated, and had to be mended. Ashpits were removed and corporation bins provided. The yards, basements and passages had to be concreted and the staircases and passages whitewashed, and all rooms by degrees papered and painted.

The object of the Tenements Company was not to provide cheap dwellings, but to make available comfortable rooms in fairly well-kept houses. It also strove to teach the rudiments of home-making to the average residents of tenement houses in Dublin. That this was needed, said The Lady of the House, was an undisputed fact: ‘The Irishwoman is the most faithful wife, the best and most unselfish mother and the worst home-maker in Europe.’

First World War

In 1992 my eldest sister Marjorie celebrated her hundredth birthday. She received messages from both the lady President of Ireland and the Queen of England. The latter because she had emigrated [to England] when she was ninety to be nearer her daughters Jill and June, Ann lives in Scotland. Marjorie was married on 1 September 1914 and widowed in 1945. During the First World War, like a great many girls from Alexandra College, she and Doris joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment and served as

FINDLATERS

Doris

nurses, cooks and ambulance drivers, Marjorie and myself in Monkstown House and Doris in the Linden Convalescent Home in Stillorgan. Mother and some friends ran whist drives for the wounded soldiers and held craft classes for them so that they had some occupation.

During the First World War my Aunt Doris, who was twenty-one in 1916, got work at the Royal College of Science in Upper Merrion Street, now Government Buildings. Her reference on leaving shows how she coped with the strange environment of the munitions factory:

I have pleasure in stating that Miss Doris Findlater has been engaged in the manufacture of War Munitions in this College for the last three and a quarter years (January 1916 to March 1919). During this time she has had considerable experience in the operation of capstan lathes, drilling machines, milling machines, and other appliances all engaged on the manufacture of Graze Fuse Caps and Adapters and Aeroplane Turnbuckles. She has also had much experience in the use of limit gauges. For some time she was in charge of shift workers, and ultimately for some months she was lady superintendent of our work until our contracts terminated.

In addition to the work she did in the shops she was also exceedingly helpful in the drawing office, where for some time she made all requisite drawings, tracings and prints of designs for jigs, fixings, chucks and special tools etc., and also of the capstan lathes which we designed and manufactured.

Miss Findlater was a most satisfactory worker in every way, capable and energetic and thoroughly reliable. She was a keen and rapid worker, and her services throughout were of the very greatest help to us. I would like to add my appreciation of the spirit with which she came forward to help us at a time of great national need, and which animated her work throughout.

Signed by the Professor of Engineering and dated 27 March 1919.

The tiger shoot, Nepal

1920 *

* Compiled from Doris’ letters home by my sister Grania Judge.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Muzaffarpur

My dearest Family,

I had a marvellous time at the shoot, we got three tigers and I saw one out in the open, wasn’t it great. Altogether we got 3 tigers, 1 leopard, 2 sambhur (deer), 2 ceetal (spotted deer), 3 Nilgai (antelope), 2 pig, 30 peafowl, 2 jungle cocks, 5 black partridge, 2 ducks. I enjoyed every minute of it. I was extraordinarily lucky to have been asked as it is a shoot that anyone would give their all to be asked to. It was done on an enormous scale, like a Rajah’s shoot.

There was Mr & Mrs Wilde. He is under-manager of the estate. Mr & Mrs Hill & Mr and Mrs Murins, both planters and Judy and Irene. [He was Julius Elms, high up in the Indian Civil Service and Irene was a sister of Jimmy Carnegie, Secretary of the RDS]. Major Davis, an ex Major in the l6th Lancers, who is first out for the cold weather like me. He is mad on photography, he took cinema photos of the shoot! He also has 2000 roses and buys all the new ones. He lives in Scotland and has a shoot there. He has just been left £5,000 [just £140,000] a year by his mother. They all thought him most suitable for me but after a day in the howdah with him I decided it couldn’t be done!! However we hope to meet in London to compare photos if we arrive about the same time!! There was Mr. Cameron—the Forest Officer of the District, another Scot, with piercing blue eyes and sandy hair and red moustache. A bit old but I wouldn’t have guessed it!! I went two days with him in his howdah as he was awfully interesting and directed all the shoot but I was afraid the day would be fatal so I didn’t risk it—aren’t men fools?? I am also to meet him in London as he gets home in April too!! And there was a Wattie Ross, a middle aged planter and Mr Collins who was here for the meet. I made it 15. As I was the only unattached female I was unmercifully teased. I never met such matchmaking people in my life!!

The camp was a topping one. The tents were pitched in a mango grove. They seem to have grown small groves of mango trees for camping grounds years ago as they give very dense shade.

Thursday morning, 10th, we were up early and had breakfast at 8 o’clock and set off on elephants at about 9 o’clock. This was quite a different sort of shoot to the Christmas one. Here it was tall grassy jungle and we had 36 elephants!!! The idea was to make an enormous ring round where you think the tiger is and gradually close in. Then when the elephants are shoulder to shoulder you will probably be able to shoot him! Naturally very few people can raise enough elephants to do this, so very few get the opportunity of seeing it.

We all went off in howdahs, 2 in most of them. I think Wattie Ross and Major Davis went in single howdahs and the rest of the elephants had pads on their backs and are called guddi-wallahs. I went the first day with Mr Cameron. It was awfully interesting being with him and he directed all the operations. We first of all made a big ring all round a dense bit of forest and gradually closed in to the centre, the elephants tearing down the branches and trees to get through the forest. We worked by degrees into the centre which was an open space with a big shallow pool in it surrounded by 10 ft rushy grass. About 5 wild pig rushed across the pool bounding through the water in an amusing way, but we didn’t shoot them, as we hoped for pan-

FINDLATERS

ther. From there we went on into tall grassy jungle stuff like pampas grass only it does not grow in dense clumps as it does at home but just like a field of oats spread out for miles and about 15 ft high. Mr Cameron shot a Nilgai or antelope and we got lots of peafowl.

We had lunch out under the trees and it was really sumptuous to eat. We had cold ham, spiced beef and meat or game pies and sometimes cold peafowl and partridge, lovely lettuce and two large bowls of salad (tomato, beetroot, potato, peas and dressing), fruit salad, a stilton cheese and a mild one, an enormous plain plum cake, celery, cream crackers, lemon squash, soda beer, whisky and plain water, cigarettes and cigars!

It really was marvellous fun—After lunch we beat back to camp getting there about 4.30 to find tea laid out on tables under the trees—after tea the men went out to shoot again on foot, quite close to the camp but didn’t get anything. I had my bath and lay down on my bed and went sound asleep until nearly dinnertime 8.30. After dinner there were two tables of bridge and the rest of us played some game.

Doris’ hunting expedition in Nepal in 1920. She is in the centre of the lower picture.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Friday 11th we packed all our clothes etc. up before breakfast as we were moving camp that day. We moved about 6 miles further north. We just went off shooting after breakfast and went to the new camping ground at teatime and there were all the tents up, beds made, furniture arrived and tea laid and made 5 minutes after we arrived. It certainly is a wonderful country. We had 50 bullock carts, 2 bullocks to each, to move our luggage, tents, furniture etc. from one camp to the other. I don’t wonder as we had proper beds not canvas camp ones and dressing tables with ordinary swing looking glasses and big tin baths and real washstands and chains in our tents and durries on all the floors. We also had 6 cars with us and a sort of matting garage, which they moved from place to place. I don’t know how many servants we had, it must have been about 130 as each bullock cart had a man and each elephant had one or sometimes two and there were dozens for our camp.

On Saturday 13th I went with Mr Cameron. We beat for about 300 yards gradually closing in the circle all the time. When we were about 30 yards from the stops some of the elephants began to scream and trumpet. Mr Cameron shouted orders and a few of the elephants tried to refuse to go on. Suddenly there was a wild rush in the grass from near Mr Wilde (No. 1 Gun) right round past us within 5 yards of our elephant and on to Judy, next gun to us (No. 8), where it tried to break through the ring. He fired and it turned back to Mr Wilde who fired twice and hit it. It then rushed back roaring horribly and Guns 4, 3 & 2 each fired and it broke through the ring between Guns 2 & 3 and jumped across the drive and fell dead just beyond. It was wildly thrilling. It was shot through the lungs, leg and side. It was great as everyone had a chance of hitting it. Mr Wilde got in the first shot, so it was his tigress.

Mr Cameron & I went back to shoot the buffalo which the tigress had eaten some of but hadn’t killed. We came across it suddenly in the grass. Our elephant was so worked up, it got frightened and stampeded wildly. However, the mahout forced it back and Mr Cameron put an end to the buffalo.

The Shoot continued for some days but I had to leave. The motor run through the Jungle providing one last thrill. In the pitch dark we saw two bright green eyes shimmering in the middle of the road a little distance ahead. Of course we all gasped ‘Tiger’! But—praise be! It was only a harmless deer and we reached our journey’s end safe and sound.

Home from the excitement of tiger shooting, Doris got herself a job as manageress of the catering department in the Bank of Ireland. That was from 1928 to 1930. Her duties comprised arranging dinners or optional luncheons for a staff of about 270 and also a four-course luncheon for the directors. She had a staff of twenty-three to supervise in the kitchens and lunchrooms. She received an excellent reference.

A full life

Sheila continued:

I was of the generation whose young men that might have been looking for a wife, like brothers of school-friends and so on, all joined up in the First World War and an

FINDLATERS

awful lot of them didn’t come back. There just weren’t so many eligible bachelors around looking for young women. I make that my excuse, as I never got asked!

I realised after a bit that I had no means of support for my future. Daddy had a couple of old friends that he looked after and saw that they were all right and would help them with their accounts and so on. I thought, ‘I am not going to be one of those awkward creatures with no means of support’. So I decided that I would take a secretarial course so that I had something to offer. There was a family crisis, and that’s what happened.

I went to Alexandra College as a mature student in 1928. I had previously been there as a girl, after which I went to Switzerland to learn French. I got beautiful looking certificates from the Secretarial Training College.

The certificates attest that Sheila holds a Pitman’s Certificate in Shorthand for a speed of 90 words a minute, and the Certificate of the Royal College of Arts for Stage 2 in Typewriting, Book-keeping, Arithmetic (1st class) and Precise Writing, and for Stage 3 in French. She also obtained the London Chamber of Commerce Junior Certificate for Book-keeping (with Distinction).

Miss White, who was the head of the College, wrote a lovely reference:

I think very highly of Miss Findlater in every way, she is a gentlewoman, and she gave me satisfaction in all respects. She has many personal qualities which, in addition to her educational and secretarial attainments, will make her a valuable and efficient Secretary. She has wide interests, and is cultured and well-read. She has good organising ability, she is artistic and she has helped greatly with all the various functions in connection with the College.

Very quickly, she got a job that began as temporary, but was in the end to last thirty-two years.

Lady Meath required a secretary for about six weeks or so to deal with all the letters of condolences from abroad on the death of old Lord Meath, that was Reginald, the 12th Earl, who died in 1929 at the age of eighty-eight. Miss White thought I would be suitable. I was older than the seventeen-year old girls. I remember Lady Meath, Aileen, wife of the 13th Earl, came into Alexandra to interview me and she evidently thought I was a suitable person and there I was! She said she thought it was short-term, and that they were planning to go away. However Lady Maureen, the elder daughter, fell and hurt herself while hunting. They went away for a short time, not as long as they had planned. When they returned she rang up and said ‘Will you come back?’ and I was there for thirty-two years until she died!

The Lord Meath who died last year [1999] at the age of eighty-seven was the 14th Earl and the son of the one I worked for. He and his wife have visited me here and she came in at Christmas (1997) with a box of chocolates–so I’m not forgotten!

I became goods friend with Sheila Powerscourt. She only died about five years ago. Her daughter is Grania and she married Sir Hercules Langrishe who sadly died last year. They were a very nice pair. We did the flowers in the house for her wedding. I remember all the Powerscourt weddings. Sheila would ask whether we would do the flowers in the Cathedral or the house. We usually chose the house. We also did the

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Christmas cards sent to Doris and Sheila in the 1930s

flowers for the Guinness family christenings and weddings at Farmleigh.

When I went to Kilruddery first there were 14 indoor staff. When I left there was only the butler. It was real ‘Upstairs Downstairs’ but it was fun. We had a great experience. Lady Meath had a little sitting room and I would work there. She loved doing crosswords and when we had done the letters we would get down to the English Times crossword. Lord Meath would probably look in before he went to do whatever he had to do.

It must have been for Punchestown that they held a house party in the grand style and were having caviar. The next morning he came into the study and said: ‘What happened last night, there were no lemons with the caviar. Any little servant girl would know how to serve caviar.’ I thought, yes, your lordship has very little clue what a little servant girl knows.

From our home, Glensavage in Avoca Avenue, Blackrock, I’d walk up to Stillorgan where the bus went past. It was the Greystones bus, and I’d get the bus to the gate at Kilruddery. They had a pony and trap when there wasn’t a car, and it would take Lord Meath down to Bray Station to get into town for his meetings. He was on the Boards of the Bank of Ireland and the Irish Lights and high up in the Boy Scouts. Then they’d come back and it would wait at the gate until I got out of my bus to take me up the drive. I remember the same trap taking the present Knight of Glin to his first day’s school at Aravon.

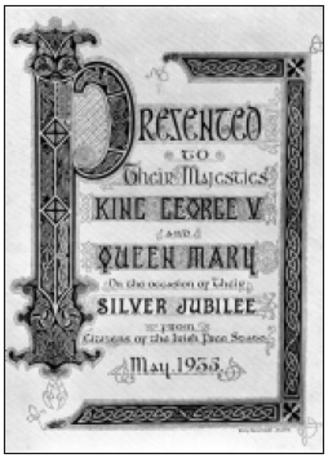

When George V and Queen Mary were celebrating his Silver Jubilee in 1935, people in England were making presentations and somebody here suggested that we, at Kilruddery, ought to do the same. But it wasn’t a very good moment politically [in the middle of the Economic War]. However, people said to Lady Powerscourt, that’s Sybil: ‘can’t you do something about it?’ She started in a quiet way, just between her friends

FINDLATERS

The presentation scroll

and acquaintances, and small amounts were contributed, five bob here and there. The Meaths were going away for a spring holiday and she said to Syb, as we used to call her: ‘You can use my Miss Findlater while we are away’, and our friend Eileen Beatty was in it too. We got going at it. Where we knew somebody of their own ilk in a county we got them to organise it. We collected quite a bit of money from those who would normally not be stingy.

Three Irish silver dish rings were purchased and West’s made a shamrock shaped case to hold the three, as they were from different periods. Eileen Beatty and I typed a book with the names of all the people who had participated and had them nicely bound. I brought it over to London for the Powerscourts. One of the papers covered the event:

‘At Buckingham Palace to-day Viscount and Viscountess Powerscourt and the Earl of Fingall presented to King George three Irish dish rings which were acquired with part of the sum of £3,300 [almost €240,000] subscribed by over 36,700 people in the Saorstát as a Silver Jubilee gift, together with an illuminated list of subscribers of Celtic design and bound in Irish poplin.

‘The King, in accepting the dish rings, asked that an expression of his sincere thanks might be conveyed to the subscribers, and expressed the wish that the balance of the money subscribed should be given to the Queen’s Institute of District Nursing in the Irish Free State and to the Lady Dudley Scheme for Nurses.’

The Irish Girl Guide movement

The scouting movement was initiated by Sir Robert Baden-Powell in England in 1909, and quickly spread to other countries. Initially Sir Robert resisted the idea of guides, but the demand was irresistible and he persuaded his sister Agnes to

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

adapt his idea for girls. Later his wife Olave devoted her life to the movement.

The Girl Guide movement in Ireland began in 1911. Companies were started mostly in the Protestant parishes around Dublin and later in Cork. Later there were companies for the Roman Catholic girls and for girls in the Jewish community, each run by guides of their own faith.

My friends and I started as Girl Scouts about 1913. We got our mother to make us khaki shirts and we bought scouts’ hats for 2s 6d each. At that time we considered ourselves to be very much a part of the British Empire and we used to tie the Union Jack onto our bicycles. We considered ourselves to be Girl Scouts. However as soon as the Girl Guides heard about us they gathered us into their movement. This was the beginning of a 40-year association with the Guide Movement. It was a terrific character- building organisation.

In the early days we learnt skills like bed making, no duvets in those days, and First Aid. We used to help out in Linden Convalescent Home in Stillorgan where wounded soldiers were recovering. We were used as patients for First Aid and Home Nursing classes given by doctors when war was declared.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and then the Easter Rising in 1916 there was neither enthusiasm nor expansion in the Scout movements which had their origins in GB and whose leaders were probably not available.

Later, my sister Doris was Captain of a Guide Company in Alexandra School and also Captain of a Ranger Company in Dublin, Rangers were aged 17 upwards. I was Captain of Guides in Blackrock and later in a school in Dublin and also a Ranger Company.

Hearing that Guide Companies were being organised in hospitals and children’s homes in England I got in touch with the Orthopaedic Hospital in Merrion Street in Dublin, where there is now a prestigious hotel, and I ran a group there of Guides and Brownies for about eight years. Nowadays this would probably be called occupational therapy. We did simple handicrafts as many of the children were in hospital for long term stays. Handicrafts became my speciality and I set up a lot of different tests for the Girl Guides to take all over the country.

Later Doris and I took on organisational responsibilities in Guiding. We were commissioners for various areas in Dublin, Doris ending up as County Commissioner for Dublin and I was a Division Commissioner. We were also on various committees. Doris was Head of Camping and I became Commissioner for the Training of Guides and I was also International Commissioner. The latter was very interesting as it entailed a certain amount of travelling and attending conferences.

The most interesting was the first world conference to be held after the Second World War in 1950 in England at Oxford. There were many interesting outings. The Guides of London had a party in the Moat of the Tower of London. The Lord Mayor invited us to coffee in the Mansion House and Lady Baden-Powell who was living in a grace and favour residence in Hampton Court invited us to tea. The most exciting was an invitation to tea in Buckingham Palace where we were greeted by the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret. Another day there was a Rally of Guides in Wembley

FINDLATERS

Ethel Warbrook, Olave Baden-Powell and Sheila, 1951

Stadium. The delegates were invited to join in by carrying their native flags, and I had the honour of carrying the Tricolour around the stadium.

During our time the Guide Cottage at Enniskerry was built on a site at Powerscourt given by Lord Powerscourt. Later there were other cottages which were used for Guides going for a week or weekends in the country and for guides from England and elsewhere.

What Sheila did not recall was the role that she and Doris played in the development of this cottage, now known as The Irish Girl Guides’ Baden-Powell National Memorial Cottage.

In a thank-you letter to Doris in July 1950 Olave Baden-Powell wrote:

I don’t know how to begin to express to you and your sister my gratitude and my appreciation of all that I have seen, and heard, and felt this week end. . . .I just can’t get over the charm of that cottage and the fact that you have raised the funds, and built and equipped it, and made it so utterly delightful. I think I realise how hard you and your committee must have worked, not only raising the funds, but in making the plans for the building itself, and gathering together all those attractive ‘bits and pieces’ which make it so homely and delightful.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

The letter ends with a little thank-you for staying at Glensavage and

‘I do so enjoy going to see your house and garden again, and altogether, though it was so very short, my visit has been a very happy one to me’.

Doris was the cottage’s first warden (1950–58).3

In 1932, the year of the Eucharistic Congress, the IGG held a large camp at Powerscourt, so that guides from the country could attend the Congress in Phoenix Park and there were also guides from the USA and European countries. I think that the American Guides found camping in the wilds of Powerscourt a bit rough!

In 1939 Doris and Eileen Beatty led a contingent of guides to a world camp in Paxting in Hungary just before the outbreak of war.

Sheila thinks that the whole face of the movement has changed enormously over the years—in many respects for the better.

In the early days when we joined the Girl Guides, it wasn’t a very popular movement, because it was still considered to be very Protestant. Lady Baden-Powell was always anxious that we should increase our membership here and when she came over, she would ask me: ‘Have you got the Catholics yet?’ It is good to see that the movement doesn’t have those divisions any more.

In 1928 a new organisation for Catholic Guides only was inaugurated. This later spread round the country as a separate movement but it was not recognised by the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts, as, in Sheila’s words, ‘it was too exclusive’. Not until 1993 was the Catholic organisation recognised by world associations and they now have a joint committee relating to World Conference and Camps.

One change which Sheila does regret is the demise of the uniform and although she accepts it as a necessity in many respects she comments:

‘In recent years, I was invited to a Girl Guides event in Christchurch Cathedral. I was horrified—in my day we would have had our shoes polished and everything matching perfectly, but that’s all gone now.

As time went by we realised that it was time to let younger women take over, as this was a youth movement so we faded out of our responsibilities by degrees, that was around 1955. After that I became actively involved in the ICA.’

As Sheila Powerscourt said in a personal letter to Sheila when she retired as International Commissioner: ‘Again all my personal thanks to you for your superlative work as International Commissioner. You and Doris and Eileen (Beatty) are The Irish Guides.’ And of her sister Doris another guide wrote:

When we remember Doris we think of one who was always cheerful and a delightful person to work with. Her sense of humour was one of the things that endeared her to her friends and it is quite impossible to describe. She was involved in so many aspects of Guiding that she had friends all through the Movement, and there is no part of Guiding that does not owe her a deep sense of gratitude. Others will remember her as she organised the refreshments at sales and exhibitions in the Mansion House. Helping

FINDLATERS

her was always fun and if it looked as though things would not be ready in time she would laugh and suggest we should stop and make a pot of tea! Those of us who knew her and loved her will always have happy memories of Doris and Sheila and be thankful for their friendship.

The Irish Countrywomen’s Association

When Sheila was young ‘handcrafts was one of my strong subjects, that is: embroidery, needlework, weaving, wickerwork and so on. After it was time to hand over our Guiding activities to the next generation I got involved with the Irish Country Women’s Association (ICA).’

Muriel Gahan was the moving force behind the ICA and many other initiatives. 4 She was a unique woman. Her passions were the traditional Irish crafts and making Ireland a better place for rural women. She and her friends established the Country Shop, at number 23 St Stephen’s Green, in 1930. She also provided a home there for the ICA (from 1937 until 1964) and the Country Markets (from 1946 until 1975). The Crafts Council of Ireland was set up by Muriel Gahan in 1971. The ICA roots lay in the United Irishwomen founded by Horace Plunkett and prominent ladies in 1910 to ‘help Irish women take up their rightful part in building up a rural civilisation in Ireland’.5 Muriel was inextricably involved in all these bodies. No. 23 became the centre of operations for the women and crafts of rural Ireland as well as a cosy, friendly restaurant serving traditional, homely fare.

Sheila was one of the group who organised the Craft end of the ICA and judged at local shows and taught crafts at the local ICA Guilds. The object was ‘to encourage crafts of good standards and help outstanding craftworkers’. ‘I travelled up and down the country judging and advising at shows. At that time education in handcrafts was in its infancy in Ireland. Muriel, who was born in 1897 and also an old girl of Alexandra College, was impulsive and would land new ideas on myself and my sister Doris, and others in the small coterie, without having thought them through.’

Sheila tells of a day in the country:

Muriel would insist on filling the car up with a load of good work to display. On arrival you had to put up the exhibition. Then you had to do a long day’s judging and advising. You escaped for a bit of lunch if you were lucky and when you got back you had to deal with complaints, such as: ‘My Granny didn’t get a prize for her socks, why not?’ By the time it was all over and packed back into the car, it was late into the night. Judges travelled in pairs and had to bear all their own costs. If far from Dublin they would be put up locally, sometimes in a warm hospitable house or cottage and sometimes shown to a cold bedroom with not so much as a cup of tea! However, it was a lot of fun and a job well done.

Sheila became President of the Dublin Town Association of the ICA in 1952. At that time the need for a residential college was top of the ICA agenda. The Findlater firm were the original Irish importers of the Kellogg breakfast cereals

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

in the 1920s and had close personal relationships with the head of their UK operation, Harry McEvoy. Sheila’s brother Dermot thought of the Kellogg Foundation, which had been established for charitable purposes in 1930. The Foundation was interested in the development of co-operative programmes in the field of agriculture and in adult education. Dermot made the connection between Muriel Gahan and their Director, Dr Emory Morris. He was impressed by her experience, her enthusiasm and the ideas that she expounded. They provided the funding that had been turned down by James Dillon, Minister of Agriculture. The result was that An Grianán in Termonfeckin became a reality and the ICA have had a good friend in the Kellogg Foundation over the years. Sheila continued her love of craft work into old age, and when the pleasure went out of travelling, she became a member of a small self-help group in Dún Laoghaire.

No chapter on Doris and Sheila would be complete without reference to Tessie Dunne, who looked after my aunts for just over fifty years, becoming part of the family in the process. Tessie was in their service from shortly after the death of their mother in 1941 until she passed away in her early eighties in January 1992. There was no compulsion in this stay well beyond normal retirement but she had a strong sense of duty and loyalty. Furthermore the aunts had bought her a house in Dalkey where she went every Saturday to join her sister and then back to the aunts on Sunday evenings. She kept the house in pristine condition and knew each of our favourite dishes. ‘Master Alex,’ she would say, ‘likes good plain food and the sponge cake for tea.’ Formalities were maintained even after Doris and Sheila moved from Glensavage to a more modest house in Glenageary. Tessie preferred the big house and the visiting Guides, horticulturists, ICA members, tea and wine merchants and the family spending a few days holiday. The grandchildren, uncomprehending of the ‘upstairs downstairs’ manners of former times, could never understand why ‘Auntie’ Tessie did not take her place in the drawing-room or at the dining-room table.

Gardening at Glensavage

In 1937 Doris was co-opted on to the Board of Findlaters and was a very regular and conscientious member for the next thirty-two years. The Board met every Wednesday at 2.30 pm in Findlaters in O’Connell Street, which to her always remained Sackville Street, as it did to many of the older generation.

In Glensavage, the fine old house in Blackrock where the family lived from 1932 to 1968, Doris’s passion for gardening developed and she created several new cultivars, and in 1966 became Chairman of the Royal Horticultural Society of Ireland.

Sheila starts the story:

We have always lived with gardens, for my mother was a keen gardener with real ‘green fingers’, and she encouraged all the family to take an interest in plants and how they grew. At Alexandra School there used to be a voluntary holiday task which took

FINDLATERS

Doris in the garden at Glensavage

the form of a collection of wild flowers each year, consisting of plants of three or four different families. As everyone getting 80 per cent got a prize, it was an easy way to get a nice book! This made one very observant in looking for the different flowers and one pored over the Revd. John’s Flowers of the Field to help in identification. A holiday away where the soil was different could be very exciting. The result was that one noticed the different flowers and soon learned the families to which they belonged. During Doris’s last year in Alexandra College in 1914, she took classes in botany and horticulture given by Canon F. C. Hayes, and at the end of the year she was awarded scholarships in both.

There was always plenty to be done in the garden at home, first, at Melville in Blackrock, then at The Beeches in Glenageary (where there was a large rose garden and a long herbaceous border) and then at Glensavage in Blackrock. During the early years, Doris was interested in roses, and George Dickson of Hawlmark Nurseries in Newtownards, named a rose for her, but unfortunately, it soon dropped out of circulation. From the classes with Canon Hayes grew an interest in propagation, and it was probably from his lectures that Doris became keen on hybridisation.

I cannot remember when she started to hybridise daffodils—possibly some of the

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

One of the Glensavage nerines (The Irish Garden October 1999)

flowers set seed one year and she sowed them. This was the time when Mr Richardson and Mr Guy Wilson were producing many fine narcissi, and the latter encouraged Doris to hybridise. She showed for many years at the Royal Horticultural Society of Ireland and the South County Dublin Horticultural Society shows, and won many prizes, including some for her seedlings. In 1961 she took some seedlings to the Royal Horticultural Society show in London and won some prizes. Later, she often judged daffodils at various shows.

Doris and Sheila’s garden at Glensavage was the magical setting where I spent many happy weeks in my youth. I remember the flowers and borders and butterflies and bees, and frogspawn and little sailing boats in a great big pond sheltered by overhanging trees and plants and the sun dappling through; all memories fast fading into the nether regions of the memory. The big attraction was the large natural frog pond ideal for sailing little boats and yachts amongst the tadpoles.

How it appeared to an outsider was recorded in The Irish Times in 1964 by Nora Reddin:

FINDLATERS

ishing and being added to every year.

A tree-shaded avenue leads to the house, which faces east. In June the house wall on this side is garlanded with roses: the deep red Allen Chandler, the creamy Alberic Barbier and the warm Shot Silk. Here too is the charming bunch-flowered yellow Banksian rose which climbs into a slender tree, grown from a cutting by Miss Doris Findlater.This tree is Azara Microphylla which has dark foliage something like Box, but of more graceful habit, and small flowers growing behind the leaves and smelling of vanilla. Opposite the hall door is a very well grown Eleagnus with its beautiful deep-green and golden foliage. It is beloved by flower arrangers and as it is an evergreen is excellent value all the year round. To the right is a lawn with two very beautiful old cedars making a background for the winter-flowering cherry, Subhirtella Autumnalis, and the later white-blossomed cherry Yedoensis.

On the south wall of the house, a wisteria has climbed to the roof and through it grows Clematis Tangutica, one of the most attractive of all the family with its yellow flowers rather like Shirley poppy buds and silky greenish-silver seedheads. Further along this wall is a peach and in a sheltered corner a grey-leaved Teucrium Fruiticans and two kinds of Abelia—Grandiflora which has rosy trumpet-shaped flowers and the most graceful shiny foliage and Schumannii with mauve flowers. . . .

This year she and her sister decided to make a new annual border and it is still gay and colourful. ‘We like to grow them in boxes first and then plant them out. Otherwise the slugs get in first.’ Amongst the annuals they have a delightful daisy-like flower, Arctotis Grandis, a glistening silver-white with dark blue central zone. Another rather prim daisy-like flower they grow is Layia Elegans, yellow with a neat white border to the petals. Its familiar name is ‘Tidy-tips’. They have a new petunia too, the true red ‘Fire Chief ’.

Nasturtiums are enchanting but a great nuisance because of their persistent roving habits. Here they have a non-rampant dwarf variety which is deep rose-madder in colour. Something quite new to me anyhow.

Beyond a low wall of pink brick there is another lawn that narrows between two wide herbaceous borders still full of colour from clumps of Michaelmas daisies, phlox and golden helianthus. I noticed too a fine plant with elegant flowers the colour of good country butter! It is Kirengoshima and would be a lovely flower for arrangement.

Like all really appealing gardens, this one has not too formal an atmosphere. The kitchen garden is alongside the flower garden—the apple trees laden with fruit. Scarlet and white-striped dahlias grow here, and a pretty rose like those one sees on old china tea-cups. It is called Perle d’Or. There are also many fragrant shrubs, including a large Viburnum Burkwoodii, which has fresh pink heavily scented flowers in spring. They have a Chimonanthus Fragrans too—a mass of blossoms in spring, with an elusive sweet scent. White lavender grows along with the commoner purple type.

This is a garden that is of interest all the year round and where many unusual things have been grown from cuttings. Its owners, as well as being greenfingered are devoted gardeners. It has a sense of leisure but I feel that it is only visitors who relax here as so much thought and hard work must have gone into its making.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Doris was a member of the RHSI and she served on the council for a number of years and was Chairman in 1966. She was elected an Honorary Life Member in 1975. She was a member of the South County Dublin Horticultural Society, and served as President for two years. In 1980 she was elected an honorary life member of the Society. She was also a member of the RHS for many years and attended some of the shows when she was in England.

A serious plantswoman, Doris began to hybridise daffodils, but found it difficult to produce good results on a relatively small scale. After daffodils, Doris turned her attention to hybridising nerines and named one ‘Glensavage Gem’. This was technically more difficult, as at that time there were few different bulbs available, especially in Ireland. Most people growing or showing nerines in Britain at that time were owners of large gardens with a staff of gardeners. Finally the Nerine Society was formed, Tony Norris being the secretary. Doris and he began a correspondence which lasted until her death.

During the 1960s he came to Dublin for a business conference and asked if he could come to see her nerines. He was so thrilled with ‘Glensavage Gem’, that he asked her to give him an offset of the bulb when one was available. This she did, and a year or two later, he showed the flower at an RHS show, where it was awarded a Preliminary Certificate. One year she took specimen blooms to the London show, but unfortunately that year there were no competitions, the Nerine Society putting up a combined stand of blooms instead. Some of the Dutch growers took an interest in her bulbs having seen them at this show.

There is an article about Doris and her nerines in An Irish Florilegium II, with paintings by Wendy Walsh,* of two of her cultivars: ‘Glensavage Gem’ and ‘John Fanning’.†

When Charles Nelson came to see the nerines one day he noticed an uncommon Daboecia growing in the garden. As Sheila remembered:‡

Being very interested in heaths he asked me about it. I confessed that we had found it in Connemara while eating our lunch near a wild mountainy road. It was a young plant, and though we knew we should not dig up native wild plants, we felt it might be lost in such a situation, so we brought it home. A year or two later, when driving along the same road, we found a cartload of rubbish had been emptied at the spot where we discovered it. Dr Nelson realised that it was a new variety, and later had it registered with the International Heather Registration Authority under the name ‘Doris Findlater’.

* An Irish Florilegium II, Wild and Garden Plants of Ireland with 48Watercolour paintings by Wendy Walsh and notes by Charles Nelson. London: Thames and Hudson 1987. Wendy Walsh has illustrated several books including An Irish Flower Garden (1984), The Native Dogs of Ireland (1984), and a book on the flora of the Burren. She was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society in 1981.

† John Fanning, one-time Assistant Keeper of the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin and a well-loved figure in Irish gardening circles. He died in 1971.

‡ Dr Charles Nelson, one time taxonomist at the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin, Chairman of the Heritage Gardens Committees, foundation chairman of Irish Garden Plant Society and author of several academic papers on botanical and historical subjects.

FINDLATERS

Each of our gardens were very different but all of them were full of colour and interesting plants—perhaps not planted in a well-planned design—often plants were popped in wherever there was an empty space. Many of these came from cuttings or ‘bits’ from the gardens of friends. If you were uncertain of the proper name of the gift you would call it after the giver—John Fanning, Ralph Walker* and so on, and Doris also loved to share her treasures with her friends.

Our gardens were always full of flowers but they were also full of memories of friends and their gardens. What a lot of happiness can be found in a garden.

Doris and I also belonged to the South County Dublin Horticultural Society and she was President of the Society for two years. Later when I was eighty-nine, I was elected President and held office for two years. I had suggested that they should find someone younger but the Council insisted!

Doris described her experiences with hybrid nerines in an article written in 1974:

I had been growing Nerine bowdenii in the garden from about 1950 and I found it produced seed very easily. There seemed to be quite a lot of variation in the seedlings produced, but not much variation in the colour—I was not very fond of the rather hard pink. In 1957 I got some bulbs of Nerine ‘Corusca Major’ from Guernsey; it is a good hybrid from the original Guernsey lily (Nerine sarniensis), scarlet, with a lovely gold sheen when the light falls directly on it. The grower sent full instructions about how to pot them, only covering the bulbs halfway up and not watering them until growth had started.

I must say this species is inclined to be shy about flowering and one must not be disheartened if all the bulbs do not flower every year. The flowers appear before the leaves in September or October. When the buds appear, you give the pots a good soak by standing them in a bucket of water for an hour or so when they start into growth. The leaves go on growing until about May, when they turn yellow and dry off. Leave the pot in a sunny place in the greenhouse to bake during the summer until the bulbs start into growth again in September. In a very hot year such as this [1974], you could water them about once a month to keep them from shrinking. Nerine sarniensis bulbs are not hardy and must be kept in a frost-free greenhouse in the winter.

Now I had material for hybridising; it is quite a simple operation. Take the pollen from the stamen of one flower and put it on the stigma of another flower of a different variety or colour. Some breeders cut the blooms and let them mature in water, but I find they ripen better on the plant. They are inclined to damp off in water, but once they are ripe, they stand quite a lot of hardship. When the seed has developed and is ripe (ready to fall), sow it. I have found it best to sow the seeds on the surface of a pan of John Innes No. l compost and anchor them with coarse sand or vermiculite, but not bury the seeds. Cover with glass or cellophane and stand the pan where it is warm (the experts say 70 degrees F, but I found the sitting room or kitchen quite satisfactory). The seeds germinate in a few weeks; they send out a little stem and the bulb forms

* The late Ralph Walker was the owner of Fernhill, Sandyford, one of the finest gardens in south county Dublin. It is open to the public in the spring, summer and autumn.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

at the end of it. The seeds of different varieties vary considerably in shape; those of Nerine bowdenii are round and quite big and may be green or dark red. In many other varieties, the seeds are green and pear-shaped. I have occasionally forgotten to sow seed, and when I found them months later, they had already formed their little bulbs and all I had to do was plant them in pans.

For the first year you may only have one leaf on the little bulb—the second year, two or perhaps three. I leave them in the pan for two years without disturbing them. Don’t let these small seedlings dry off in the summer. The third year I pot up the bigger seedlings singly in small pots or sometimes three in one pot, or well spaced out in a larger pan for another year (still in John Innes No. 1), always covering the bulb only halfway up. Some grow quickly and make great big bulbs, and a few flower in the fourth year, but they do not generally flower until they have formed six leaves and that may be in the fifth or sixth year.

It was in 1965 that I had my first thrill when two of the seedling bulbs flowered and each produced a new type of flower. One was crimson-rose in colour and the other rose-opal. . . .

I went on crossing some every year with varying success; the Glensavage strain does not bear seeds so it was mostly the scarlet Guernsey lily seeds that I used. About 1969 I got a pot of Nerine flexuosa ‘Alba’ from Mr Ralph Walker, and crossed it with the scarlet Guernsey lily. A new crop of seedlings resulted, the first flowering in 1973. I hoped for a startling red and white striped blossom but so far they have produced rose-flamecoloured flowers, the colour of the rose called ‘Super Star’. However the petals are more curled and narrower than my other seedlings.

The outdoor species Nerine bowdenii which flowered so marvellously this year [1974] and grows freely here is, according to scientists, parthenogenetic—that is, it forms seed without fertilisation of the ovules. In fact you often notice the seed swelling before the flower opens. This means you are unlikely to get a new variety from its seed, but if you use its pollen on another variety, the progeny is likely to have its size and vigour. It was by putting the pollen of the pink Nerine bowdenii on the stigma of the scarlet Guernsey lily, that I got the Glensavage hybrids.6

Sheila presented Doris’s collection of nerines to the National Botanical Gardens in Glasnevin, replacing their own collection, which was destroyed by frost in about 1930. They are on view to the public as they come into bloom in the late summer.

FINDLATERS

Appendix 1: Mid-winter flowers at Glensavage

November, at the latest, for most Irish gardeners, heralds the end of the season but not so for Doris and Sheila as The Irish Times of 28 January 1955 explains:

Two lists of mid-winter flowers have been published recently. The list from Miss Findlater contains the names of the flowers she could pick in her garden in Glensavage, Blackrock, on January 5th. It is a very interesting and comprehensive list of 87 items, and is remarkable for the number of flowers that have lingered on from the summer or autumn. Summer seems to die slowly in Blackrock. It is characteristic of our winters that severe frost rarely occurs before Christmas, and provided that our gardens are well-stocked we should be able to pick an interesting mixed bunch of flowers up to that season. Doris’ list of mid-winter flowers:

Anthemis tinctoria; Achilleca Gold Plate; Achillea argentea; Dimorphotheca Nerine Bowdenii; Forget-me-not; Tagetes pumila; Cornflower; Campanula; Schizostylis Mrs Hegarty and Schizostylis Viscountess Byng; Gentiana acaulis; Cxalis; Brompton Stock; Potentilla; Candytuft annual and perennial; annual variegated Thistle; Aconite; Crocus; Snowdrop; Onosna; Lupin; Nigella; Primrose; Polyanthus (various); Viola; Pansy; Valerian; Erica carnea (various); Bergenia Pink; Saxifrage apiculata; Eripsinun mauve and brown; Scabiosa annual and caucasica; Helleborus niger and Lenten; Vinca alba; Calendula; Aubretia; Hollyhock; Welsh Poppy; Violet; Parma Violet; Dianthus (various); Azara microphylla; Cydonia japonica; Escallonia macrantha and Donard Seedling; Prunus subhirtella autumnalis; Pulmonaria; Fuchsia dwarf; Mahonia Bealei; Olearia; Buddleia auriculata; Garrya Elliptica; Rosemarinus prostratus and Miss Jessop; Iris stylosa; Gumcistus; Viburnus fragrans; Burkwoodii; Grandiflorum and tinus nirtum; Hammelis mollis; Ceanothus Gloire de Versailles; Chimonanthus fragrans; Lonicera Standishil; Salvia Grahamii; Hypericum various; Jasminum nudiflorum and revolutum; Roses various; Lithospermum rosemarinifolus; Spartium junceum; Genista (species); Forsythia; Chrysanthemum maximum; Teucrium fruticans azereum; Veronica hulkeana; Hepatica; Camomile; Antirrhinum and Prunus Davidii.

MY AUNTS DORIS AND SHEILA

Appendix 2: Miss Doris Findlater’s Nerine Cultivars7

[This is an abbreviated version of the technical notes by E. Charles Nelson to my aunt’s article.]

In her work with nerines some 30 hybrid seedlings were produced of which the best known are:

-

‘Glensavage Gem’–flowers claret-rose [021 or geranium lake 20/1]. The stems are tall, to 26 in. and the perianth is 21¼ x ⅜ in.

‘Glensavage Gem’ is the only Nerine cultivar raised by Miss Findlater to receive an award, when shown by A. Norris of the Nerine Nurseries, Welland, in October 1968, it received a Preliminary Certificate of Commendation. Miss Findlater sent Norris the bulbs in May 1967. The cultivar has been officially named in the Nerine Society Bulletin 2 (1967: p. 11). In Bulletin 3 (1968: p. 3), Norris remarked that he had high hopes for this cultivar. In a letter to Miss Findlater dated 23 October 1969, he stated, ‘I really think that [‘Glensavage Gem’] has a better head than anything else I have got.’ Earlier, on 10 October 1968, he had congratulated Miss Findlater on producing a completely new strain of ‘Nerine’. In January 1976, Mr Norris remarked that ‘Your “Glensavage Gem” continues to produce one of the best flowers in [my] collection and I like it very much’. The praise continued in a letter dated 22 February 1977–‘I think “Glensavage Gem” is quite one of the best’. In August 1982, after Doris Findlater’s death, Tony Norris paid this tribute to her–‘[She] will always be remembered by many who grow Nerine for her hybrids–especially “Glensavage Gem” which is now growing in many lands. I have sent bulbs of this variety to America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand . . . I rate it amongst the best. However it is a pity that there is no Nerine that carries her name . . .’ It is still in cultivation and is depicted in Walsh and Nelson, An Irish Florilegium 2 (1988).

-

‘Glensavage Glory’–flowers rose opal [622/1]; stem to 30 in., leaves c. 13 in. long and 2 in. broad, mid-green; perianth segments 2¼ x 7/16 ins. Name not published.

-

‘Silchester Rose’–flowers in late September, leaves mid-green about 7½ in. long, ¾ in. across; stem to 20 in., perianth segments 1½ x ⅜ in.

-

‘John Fanning’–flowers in late October, leaves dark green, bluish on the back, 12 in. long, to ¾ in. across. Flowers full claret-rose [HCC 021 to 21/1], segments 2 x ⅜ in . . .

Nerine John Fanning’ is depicted (with ‘Glensavage Gem’) in An Irish Florilegium 2 (1988).

-

‘Sheila’–leaves 6 in. long, dark-green, stem to 20 in. Flowers rose-opal with a slightly, deeper stripe which is crimson [HCC 22/1 fading 22/2]. Perianth segments 2 x ⅜ in., early September.

Miss Findlater took this to the Royal Horticultural Society in London in 1971, where it was greatly admired. In particular it impressed H. J. Paul Wülfinghoff of Rijswijk in

FINDLATERS

Holland, who asked to purchase bulbs of it; Miss Findlater sold bulbs to Wülfinghoff Freesia BV in January 1974. She also supplied Wülfinghoff with the Glensavage Nerine cultivars No. 1 (‘Glensavage Gem’) and No. 10 (‘Alfino’). It is not known if ‘Sheila’ is still in cultivation in Holland.

Notes and references

- Church Gazette, February 1942

- The Lady of the House, November and December 1913 and January 1914, ‘Woman’s Life in the Dublin Slums’

- History of The Irish Girl Guides’ Baden-Powell National Memorial Cottage, Enniskerry, Co Wicklow, booklet compiled by Doreen Bradbury, 1999

- Geraldine Mitchell Deeds not words, The life and works of Muriel Gahan Dublin: Town House 1997 pp 153, 173, 177

- IAOS Annual Report 1910 quoted in Trevor West Horace Plunkett–Co-operation and Politics- Gerards Cross: Colin Smythe 1986 pp 102-103

- Moorea—the Journal of the Irish Garden Plant Society Vol 7 Sept. 1988 pp 27–32

- Ibid.