FINDLATERS

1960s Shop Designs

Main Street, Malahide 1917‒69

2 The Green, Sandymount 1897‒1969

65 Upper Dorset Street 1906‒69

14 Main Street, Dundrum 1945‒69

28 Main Street, Blackrock 1879‒1969

The branch shops not pictured in the book are 47 Ranelagh

1922‒60 4–5 Wicklow Street 1934‒68 Main Street Cabinteely

1944‒68 3+4 Mount Merrion Gardens 1950‒68 Stillorgan Shopping

Centre 1966‒68

8 Main Street, Bray 1901‒69

16. From old Findlaters to new

In our family business, as in so many others at the time and since, the eldest son went into the firm, and this had been my destiny since birth. I was born in a Hatch Street nursing home (known appropriately as the Hatch), in the street in which I now work, on 25 September 1937. We then lived in a house called Glann in Gordon Avenue, Foxrock. I have distant memories of playing in the river that flowed through the bottom of the garden. In 1941 we moved a couple of miles to Abilene, a dilapidated farmhouse on the Blackrock side of the Bray road. The house was then in a very run down state, almost uninhabitable, and my grandfather Harry Wheeler is reputed to have commented that he would not have his daughter live in such conditions.

Abilene stands on three acres. To the west there’s a large walled vegetable garden which in those days had every type of fruit and vegetable in between a great network of pathways. Daddy had a mechanical cultivator and could be heard at work early in the mornings while we lay on in bed. We also had a full-time gardener. Surplus produce and masses of flowers from the herbaceous borders would go into Daddy’s car and I am sure were given away when he visited ‘the Incurables’, now the Royal Hospital in Donnybrook, or to the secretaries and staff in O’Connell Street. Other mornings he used the dogs, Bingo and Popeye, to herd us out of bed to the strains, played at full blast on the record player of ‘Oh What a Beautiful Morning’ and into the Bentley, for a shivery early morning cold plunge at Seapoint or Killiney, telling us that the iodine in the seaweed was very good for our health.

Later he hired Jock and Joe, whom he saw excavating a filling station site in Blackrock, to dig a great big hole in the middle of the ‘Little Garden’ to the south of the house and turned it into a perfect and ever-popular swimming pool amongst the flowers and roses.

From an early age I was instructed on the workings of the Atco mower and it was my job during the holidays to keep the tennis court in front of the house mown, rolled and marked in readiness for the frequent games. The ponies and a donkey in the fields between the house and the road were the responsibility of my sisters and had their stable in the ‘hen-yard’. The hens provided us with all the eggs we needed and some were set aside in waterglass for winter baking.

FINDLATERS

Most large households had their own hens in those days and Findlaters supplied a full range of feedstuffs for all types of farmyard animals.

In the basement, which was only slightly below ground level, was a magnificent Hornby 00 electric railway covering the area of two rooms. Over our sixty years’ tenure of Abilene this set-up has given hours of pleasure. Friends and relations would cycle over from all over the southside and parents knew that their young ones were having great fun (totally unsupervised) in these lovely surroundings. Mother always had an abundance of cakes and scones laid on for us at teatime. The mere mention of Abilene conjures up very happy memories in so many of our friends.

At the age of six I started at Greencroft School in Carrickmines. The school was run by Marjorie and Olive Creary and was a lot of fun. One of my first palgirls at the school was Jennifer Hollwey who later married the banker John Guinness and survived a harrowing kidnap. The school struggled with my reading problem, as one report records: ‘Reading is his great difficulty and he does not seem to have any great desire to be able to read, though he enjoys reading the stories he knows by heart.’ In contrast writing was ‘very good’ notwithstanding that I had been changed from left-hand to right-hand under Father’s instructions, who was heard to comment ‘I will not have a left-handed hockey player in the family.’* It did, of course, give me the benefit of being ambidextrous, useful when casting a fly, playing a tennis ball or doing a bit of carpentry. In September 1946 I started as a boarder at Castle Park School in Dalkey which I thoroughly enjoyed, in spite of my first letter home ‘I don’t like this school’. But a month later ‘I am getting to like the school better’! Some of my letters had a request for more tuck. I was in an advantageous position. The Findlater van was frequently in the school yard where we played between classes, making deliveries to the school kitchen, and a quiet word with the co-operative van driver usually brought the necessary response. Otherwise my letters spoke about the matches against Aravon, St Gerard’s and the new school in County Meath, Headford, whom we walloped in the first cricket encounter. We made 164 runs for 9 wickets and they made 7 runs all out in the first innings and about 10 for 6 in the second. But what impressed me was that they served ice-cream after the match. My school reports recorded that arithmetic was my strong subject and Latin very satisfactory. However, reading was still a problem.

Castle Park in those days was considered by some to be the last outpost of the British Empire. When John A. Costello declared us a Republic in 1947 we are reputed to have played ‘Oh God our help in ages past’! The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was a day of celebration. The headmaster, Donald Pringle, made a quick visit across the border to acquire the appropriate coronation shields and emblems, and badges showing the Queen’s head and pencils with the dates of the kings and queens of England were distributed at breakfast. The old boys’ magazine reported that ‘the school now possesses a first-class wireless set and

* This was impossible, for unlike hurling, hockey is only played on the right-hand side of the body with the stick held left hand above the right hand.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Abilene enriched by the spring display of crocuses and snowdrops

loudspeakers in the classrooms relayed the BBC programme to which the whole school listened most of the morning.’ After a special lunch, the afternoon was spent on Killiney beach after which prizes were given for the best floral design in the house gardens and the best coronation paintings. However, not everyone felt so euphoric about the event and when the schoolrooms were opened up the next morning it was discovered that all the Union Jacks had been torn up and the picture of the Queen was missing, later found burnt in the woods of the school grounds. The boys were exonerated when footmarks of the intruders, called vandals, were detected outside!

In the autumn of 1951 Mother took me on a voyage across the water to a village plumb in the middle of England called Repton. I was very homesick and burst into tears in Manchester when I could not understand their dialect. Repton is an old English public school founded in 1557 and included much of a 12th-century Augustinian priory set in the village of Repton in Derbyshire, once the capital of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia. In the 20th century three of the school’s headmasters went on to be Archbishop of Canterbury: William Temple 1942–4, Geoffrey Fisher 1945–61 and Michael Ramsey 1961–74. Fisher had also been a pupil from 1918 to 1923, and his son Frank, later headmaster of Wellington, taught me hockey and elementary soldiering (in the Combined Cadet Force) at Repton. The school did not have a noticeable religious bias but attendance at morning chapel and evening prayers was obligatory. Repton was chosen for me on two counts: first Donald Pringle was an old boy and recommended the school to my parents, second, one of my Aunt Sheila’s best friends was married to a house-master there, Henry Davidson. We likened him to the character of the ageing old school-master, played by Robert Donat, in the 1938

FINDLATERS

film shot in Repton, Goodbye, Mr Chips, such was his loveable and caring character.*

I enjoyed my time there. The object of sending me away was to try and make a man out of me. I had too many privileges living and schooling around Dublin. The public school adventure started at the beginning of each term when our parents delivered us into the charge of the purser at the B&I gangway in the North Wall for the 7.45 pm sailing. On one occasion we were late leaving home and my father phoned the ship and requested the captain to delay the sailing until I was safely deposited on board. We travelled to our various schools across England by rail having much fun and mischief on the way. For example, sitting in the opulence of the Grand Central Hotel, Manchester waiting for our connection, we got up to such pranks as asking the callboy to page, in his high-pitched voice, for ‘Mr I. P. Freely’ and other such characters, putting us into stitches of laughter.

Repton excels at cricket and association football producing many of England’s great amateur players. My life centred around the playing field, and a wide variety of sports: hockey, cricket, football, squash, tennis and cross-country running. My father had occasion to dictate a letter to remind me that a certain amount of academic study was necessary, but he never followed up the subject. His questioning focused on the playing field. I did just enough study to gain entrance to Trinity, which my father very reluctantly allowed, but anything in excess of a pass was considered a waste of good sporting time!

I could not find a course that interested me and again settled for the playing field and remained on the college books for four years, seldom taking an exam and never failing! In those days there was no business school, a commerce degree was taboo to my father, as was the wearing of the Trinity tie, and language courses were a continuation of text book study experienced at school and with no oral facilities. Trinity to me was hockey in College Park, wonderful tours to English and Scottish universities, attendance at the occasional debate at the Hist, and pints in the Lincoln Inn (the pub outside the back gates) or Jammet’s back bar, and with fellow Knights of the Campanile. There was a bit of the Ginger Man style still in College in those days. Part of the deal with my father was that I undertake a full apprenticeship in Findlaters at the same time. So from the first of May 1956 my apprenticeship started and Daniel Skehan, manager of O’Connell Street, acknowledged that first week:

My dear Master† Alex,

I have great pleasure in presenting you with your first ever Time Card from 1st to 4th May 1956, inclusive, together with your first complete Time Card for week ending May 11th 1956.

May I take this opportunity of offering you my heartiest congratulations on your entry into the Firm of Messrs. Alex. Findlater & Co. Ltd. and I wish to lay special

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

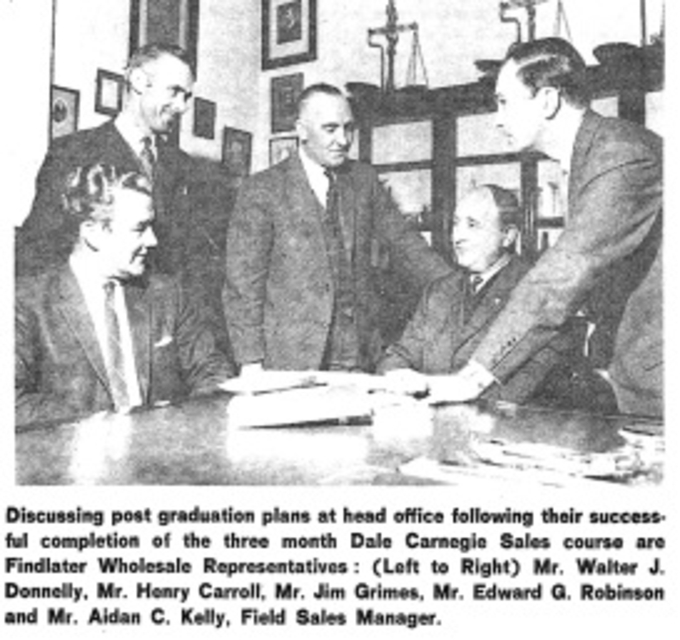

Findlater Herald. November 1967

emphasis on the fact that you carry the Firm’s famous name. I now wish you many happy, successful years in the Firm which you are, I hope, destined to control some day,

Finally, I would like to have it placed on record that I am honoured to be your first Manager. Yours faithfully,

Daniel Skehan.1

* A view of Repton through the eyes of a celebrated Irishman, Terry Trench, founder of An Óige (Irish Youth Hostel Association) is given in Nearly Ninety, Meath: Hannon Press 1966.

†On my 21st birthday I became 'Mr Alex' and it was considered insubordination for all but the most senior managers to use the term 'Master'!

Feargal Quinn tells a story of my apprenticeship. ‘I learnt recently of a little story about Alex when he was serving his apprenticeship in their tea and coffee blending factory in Rathmines. Alex was given a task at the coffee roaster. Something went wrong. He took his eye off the ball, pulled the wrong lever, and mixed a ton of unroasted with a ton of roasted beans. Now, that presented a bit of a problem—but not so for Mr Findlater Senior. He just said to Alex: ‘Your problem’—and Alex spent the next week sorting the roasted from the unroasted beans!’

One of my first jobs in Findlaters was a week spent in a lock-up store, some 8 feet by 4 feet, breaking up Early Mist and Royal Tan chocolate bars. Joe Griffin, the celebrated owner of the Grand National winners Early Mist (1953) and Royal Tan (1954) had fallen from grace and

FINDLATERS

the only outlet for the bars was as broken or cooking chocolate without the wrappers!

After six months it was thought that I would benefit from a trip to Donegal with senior traveller Mattie McElroy to experience at first hand the techniques of selling spirits, wines and on this occasion introducing Irish-bottled Tuborg lager beer to the pubs and hotels. I have always suspected that the object of the trip was to introduce young Master Alex to drink, so worried was father at my seeming lack of interest in all shades of the product (as it happened this attitude quickly changed when I had been in Trinity for a term or two).

And so it happened on the first night in Jackson's Hotel, Ballybofey.

The various company representatives met there at the bar. ‘And who is this fine young man you have with you, Mattie?’ Then to the barman ‘Another Tuborg for Young Master Alex’. And after three he escorted me upstairs: ‘are you sure you are all right Master Alex?’ as I marvelled at the total normality of my state. I never looked back and I am sure he phoned my father that very night and reported mission accomplished! More seriously I was several years in the grocery buying office, learning first from Cecil Reynolds who had a lifetime of experience in the company and then with Paul Barnes whose father, and I think grandfather, had been attached to the Dún Laoghaire branch. Another stalwart who had worked his way up from messenger-boy to board room was general manager Paddy Murphy.

Findlaters had very able managers throughout the branches and head office and I hesitate to mention them here for fear of offending those whom I miss out. However, a few who may not have been mentioned elsewhere are Cecil White of Malahide who was in charge of all the fruit and vegetable departments, John McCormack, Peter Dunne, Jimmy Graham in the provisions and Jarlath Lynch and Des Holden, manager and wine manager respectively, all in O’Connell Street, and the Miss Tanners (as they were called), Ruth Bell, Polly Richardson, Violet Simpson, Anne Fahy, Helen Tracey and Rosamund Dempsey in the administration on the upper floors. In transport there were so many wonderful characters such as Joey Baker, Paddy Reddin and Jimmy Farrell and some families like the Dunnes and Christy St Leger, who lived on the premises in Findlater buildings. In charge of the whiskey house was John Parkinson, beer bottling Paddy Treacy, grocery lofts Christy O’Brien. On the road were Walter Donnelly,

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

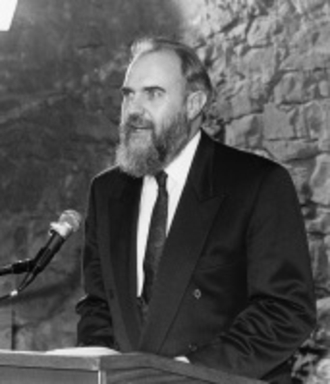

Stanley Fleetwood, Manager of the Year 1960‒61 (Photo Lensmen)

Eddie Robinson, and Jimmy Grimes of the old school, and also Noel Jordan and Henry Carroll; in the St Lawrence hotel was Ivor Williams, and managing a branch or large department were Willie Boylan (Crumlin Cross), Pat Byrne (Mount Merrion), Robert Campbell (Dundrum), Willie Delaney (Dún Laoghaire), Gerry Enderson (Dún Laoghaire), James Farrell (Dún Laoghaire), Pat Graves (Bray), Jimmy Greene (Baggot Street), Sam Hanlon (Foxrock), Tom Long (Blackrock), Dan Meagher (Wicklow Street), Johnny Murray (Georges Street), Reg Quinlan (Cabinteely), Tom

Roche (where the need called!) and Joe Whelan of Ringsend, the best provision salesman in the business.

For me familiarisation with the business had begun early. It took the form of accompanying my father on branch visits and being well-informed on most aspects of the business by school-leaving age.* Dermot was anxious to get me installed and equipped as quickly as possible. To this end I was appointed a director at the age of twenty-one—far too young. Although this was well intentioned, I could add little to the board’s collective wisdom. On the other hand, it was the finest training ground that I could have aspired to and was to give me a great breadth of experience that would stand to me in the difficult years ahead. Discussions ranged from union negotiations, personnel matters, bank relations, property maintenance and the purchasing of everything from eggs in Ballyhaunis to whiskey fillings from Jameson and Powers. Since the preference shares were publicly quoted, the company was subject to stock exchange regulations and board matters were handled in an exemplary manner.

Not only did Dermot want me to know everything about the business, he also wanted me to meet the characters of the city, from the top down to the street car-park man, an institution in those days. They would always have a good spot for his Bentley, but then he was a regular client and a good tipper. In fact Father advised me that these men were a great source of information on the welfare of other businesses in the city and who was a poor credit risk. On one of these occasions around town Father marched me in to the Dolphin Hotel to have the honour of meeting old Jack Nugent, the proprietor, in his sick bed, just before Jack shuffled off to the next world. On another he greeted Alfie Byrne, ten times Lord Mayor of Dublin, outside the National Stadium, and dictated to him what he

* Passed-down wisdom has certainly been a key to our on-going success over the ages.

FINDLATERS

should write in my autograph book—dare I accompany him without that book! He got his friend Lorcan Bourke, proprietor of the Four Provinces Ballroom, where I learnt my bar trade, to arrange a lunch at the Gresham for me to meet his son-in-law Eamonn Andrews; on another occasion he plucked me out of the grocery lofts in working garb to have lunch in the smart Russell Hotel in Stephen’s Green as the guests of the directors of the all-powerful Scottish Distillers Group. He announced the setting of an extra place with the wave of his arm and all went well until I learnt of the existence of cold soup for the first time!

He orchestrated me on to the managing committee of the Royal Hospital for Incurables at the age of nineteen where I was the only member under the age of fifty—daunting! This was to keep up the family tradition that had run through five generations. At my first meeting the aged acting chairman asked the meeting to rise in silent prayer in remembrance of the hospital’s great benefactor, Alexander Findlater; a quick nudge and a whisper from Connie Smith, the hospital’s diminutive secretary, ‘No! We are welcoming young Alex here for the first time today.’

Dermot had brought the company through from the 1930s to the 1950s and had strengthened its fabric. He had invested profits in the modernisation of the branches, the hotel in Howth, the beer bottling and in the head office in O’Connell Street (Findlater’s Corner). He left a fully stocked drinks company with prime agencies in Harveys and Tuborg. But all this, especially the heavy post-war investment programme, had cost money and earnings remained pitifully low. Borrowings peaked at £199,000 [€4.4m] the quarter he died. That was the legacy that my father left John McGrail and myself, then twenty-five years of age.

The popular belief is simply that Findlaters missed the boat in respect of selfservice. The true story is as usual more complicated. Dermot had not been in the best of health since the Emergency and had lost the incisiveness he enjoyed in the 1930s and 1940s. Many of his investments were not well thought through. Large tranches of wine were ordered with gay abandon at lunches in the directors’ dining-room. In the next two decades many good English wine merchants got into serious financial trouble as a result of being hopelessly overstocked in maturing Grands Crus Bordeaux wines. Happily the vintages Dermot purchased were good and the quality excellent. Add to this the considerable investment in bonded whiskey stocks and the credit extended to hoteliers and publicans throughout the country, the money being ploughed into the beer bottling plant and the hotel in Howth, and the company’s approaching problems become apparent. He was investing on too many fronts. There was a rationale for each, but collectively they were not sustainable. So when funds were needed for the self-service revolution the cupboard was bare.

The self-service revolution in England got under way in the early 1950s. Of course, like all such revolutions they are nothing like as inevitable at the time as they appear in retrospect. By 1960, when I was privileged to spend a month in

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Sainsburys observing their systems, only 10 per cent of their shops had been converted to self-service. By the end of the decade the figure had risen to almost 50 per cent. In Dublin Findlaters were still strong and there seemed to be a continuing demand for the firm’s traditional services. The pending supermarket invasion was only a small cloud on the horizon. The newspapers treated them as an amusing conversation point. ‘Why we do or do not shop at supermarkets’, wrote the Sunday Independent; ‘Supermarket is not for me’, reported the Sunday Press. On the other hand there was an army of competitors poised to invade our patch with new retailing techniques. Notable among these were Galen Weston,*the son of a Canadian grocer and biscuit maker, Ben Dunne, a Cork drapery retailer† and Feargal Quinn, the son of a holiday camp proprietor. Local competitor H. Williams was already well advanced.

John McGrail wasted no time in identifying the task ahead at the 1962 AGM:

The immediate and primary purpose of the Directors [is] to raise the Company’s profitability to a substantially higher level. The achievement of this purpose is no easy task. Trading conditions have rarely, if ever, been more difficult—on the one hand profit margins are reduced by the intensity of present day competition, whilst at the same time working expenses are continually growing as a result of higher wage rates and reduced working hours. The only solution to this problem is an increase in the productivity of the staff, because of course the real wealth of the company, like the wealth of a nation, is determined by the aggregate daily effort of each individual.

He repeated much of this in 1963:

This Company has taken the lead in the Retail Food Trade by introducing a Staff Bonus Incentive Scheme. Staff participation in surplus profits conforms to the most enlightened and progressive social thinking and it will undoubtedly help to engender and maintain that spirit of co-operation that is so necessary in the Retail Food Trade with its extremely high ratio of labour content. I think I may say that at the present time the state of our relations with our Employees Association and with the three Unions to which the other sections of our staff belong leaves little to be desired.

Grappling with the need for increased productivity is one thing, but retrospective taxation is another: ‘The provision in this year’s Finance Act for an increase of 50 per cent in the rate of Corporation Profits Tax is discouraging and aggravates the already difficult problem that confronts all business concerns of endeavouring to finance development and expansion from their own resources. But however disturbing this measure might be, it is less disturbing than the further provision that seeks to make this increase retrospective to 1962.’ And on top of that the introduction of a turnover tax: ‘The other innovation in this year’s

* It started as Powers Supermarkets, then became Quinnsworth on the purchase of Pat Quinn’s stores, and now, as Tesco, vies for No. 1 position with Dunnes Stores. Its pre-eminent position in recent years is much to the credit of its retired chief executive Don Tidey. It has 76 stores.

† A great Irish success story. His first drapery outlet was opened in Patrick Street Cork in 1944. There are now 60 Dunnes Stores in the Republic of Ireland and 18 in Northern Ireland. Ben Dunne (senior) used to say to me at the Curragh races, with a twinkle in his eye: ‘Dunne’s Stores better value beats them all—you, too, Alex!’

FINDLATERS

Finance Act—the provision of a turnover tax—is one that, if ratified, will impose a heavy and inequitable burden on the Retail Food Trade, and we must register our strongest protest against its implementation’. At the same time the use of trading stamps was prevalent: ‘The ultimate and inevitable consequences of the widespread development of stamp trading in this country would be an increase in the cost of living of something in the region of 23⁄4 per cent.’ And finally a rap on the knuckles for the suppliers: ‘Manufacturers of nationally advertised branded consumer goods might be well advised to devote more thought and attention to the quality and value of the goods they produce and sell, and less attention to the gimmicks their advertising experts produce and sell.’

McGrail’s comments on the turnover tax were a signal that it was not a well thought out tax. This was confirmed a decade later in the 1972 Fair Trade Commission Report of Inquiry. On the tax it said ‘The present Turnover tax system operates to the disadvantage of the independent retailer, due to the fact that there is no legislation governing the way in which the tax is collected.’ This made the tax virtually optional. It provided the opportunity for taxes collected from customers not to reach the Revenue Commissioners. Some no doubt grew rich on it.

The full Findlater

service involved canvassing for the order at each

individual house or farm, assembling it, delivering it and

getting paid a month later. Maureen

Haughey remembered how the service operated:

When we lived in Grangemore, Findlaters’ agent called once a week. This took place on Thursday afternoon and was a major event of the week and I had to be on hand for it. He would sit down, carefully write out the order, advising me on the best things available that particular week and reminding me if he thought I was forgetting something.

When the van arrived the next day, Friday, with the order, there was great excitement. The children would rush out to see what ‘goodies’ had arrived. The driver was very pleasant and would permit them to clamber all over the van and give them a lift down as far as the gate.

On one occasion when the van was stationery they accidentally pressed the starter button—but luckily the driver was close by to keep the situation under control.

Findlaters’ old-fashioned, courteous service was very much part of our family life at that time and the weekly arrivals a pleasant domestic event.

Feargal Quinn, chief executive of Superquinn, foremost amongst supermarket proprietors in the country today and head of a group with eighteen supermarkets, put it clearly in a speech in 1993:

When I was growing up the Findlater way of doing business was a byword in Dublin. It stood for personal service to the customer, but it was different—it was an individual service to each customer backed up by such good ethos as telephone ordering, home delivery and extended credit. And it was an example, I think, of what I would call nowadays the boomerang principle—running your business in such a way

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

as to make it your prime aim to get your customers to come back to you again and again and again . . . it wasn’t the Findlater approach to customer service that had reached its ‘sell-by-date’. It was the Findlater way of delivering it and the whole cost structures that went along with that.

Oh how we would enjoy such a service today! But, as our accountant Alan Kirk rightly observed, ‘On our present earnings and our financial position we cannot afford our present standard of workings, which is higher than many companies with which I have been associated where earnings are considerably higher.’

The conditions of trade turned gradually against us—first there was the abolition of retail price maintenance in 1955 and then the advent of self-service. The effect was a drop in the percentage net profit before tax from an average of 1.5 per cent to under 0.5 per cent, a very delicate margin on which to work.

| Net profit per cent of turnover | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939-45 | 1946-55 | 1955-60 | 1961-66 |

| 1.5 per cent | 1.25 per cent | 0.5 per cent | 0.45 per cent |

A government report on the industry showed that the aggregate net profits before tax for seven major supermarket multiples for the years 1968, 1969 and 1970 were 1.5 per cent, 1.5 per cent and 0 per cent. Clearly trading conditions were tough, at their worst the year after we closed our retail outlets—good timing! Just as competitiveness was hotting up in 1966 the board instructed the firm’s buyers to raise profit margins by 33⁄4 per cent or ½d in the shilling. This was the price of survival. It was calculated that the 10th round national wage increase would cost Findlaters something in the region of £15,000 [€290,000]— more than the previous year’s profit.

The national wage increases in the 1960s were fast and furious. No sooner had management come to grips with one than the next was being negotiated. However, the one redeeming feature was that the extra spending power came straight back into the grocers’ tills. Our 1962/63 accounts reflected the cost of the 8th round wage increase. 1963/64 reflected the increased purchasing power created by the 8th round up to 1 November 1964 when the 2½ per cent turnover tax was introduced. This was a severe setback to the trade and was reflected in the 1964/65 sales. At a board meeting on 24 June 1964 it was estimated that the round under negotiation would add £20,000 in the current year and £15,000 in the following year. All in all, a rough ride when the self-service operators needed fewer and less skilled staff.

| Wages as a per cent of turnover | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 1950 | 1955 | 1958 | 1960 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 |

| 10 | 10 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.8 |

FINDLATERS

Expenditure on stables, motors and cycles as per cent of turnover (an index of the cost of service) rose steadily throughout the 1950s, peaking at 1 per cent in 1963, or twice the value of net profits; thereafter it dropped back to less than 0.8 percent of turnover.

When Dermot finally said ‘No’ to the plans for the conversion of Dún Laoghaire into a large supermarket in 1960, that was it. After Dermot died in 1962 aged fifty-six, I turned to Mother and said: ‘Well, there may be one good thing out of this. Jack can now go ahead with the supermarket plans.’ It was not to be. Probably for financial reasons, McGrail adopted my father’s stance and vetoed the Dún Laoghaire development. Supermarketing was a young man’s trade; for once there was no inherited wisdom, all the experience was gained from observing another man’s successes in another country, usually the US or UK. I was twenty-five years old and impatient to be given the green light. I inevitably became a thorn in John McGrail’s side.

After Dermot’s death we all knuckled down to the task of managing the company. Findlaters’ sales began to respond to initiatives and were increasing modestly. There was plenty of emphasis on training and trips to London to learn more about self-service. The overdraft was reduced by about £25,000 from its peak. There was an encouraging profit climb from 1961 to 1964 which gave hope. Everyone was kept busy with meetings and reports. A new second layer of managers was created.

Analysis showed that (as John McGrail had pointed out in 1960) our best returns were still coming from our traditional high service branches. However, this proved misleading, in that as other service competitors closed down we received a boost in trade. It looked as if we were doing well; in fact we were simply mopping up the remnants of a fast fading trade system. Of course, plenty of analyses of sales and expenses were produced. It was quite a complex business with up to eighty retail and wholesale departments to be supervised, many with overlapping costs, so it was usually hard to see the wood for the trees. Despite short term boosts to morale, the going was tough. In the three years 1965, 1966 and 1967 Findlaters made an aggregate pre-tax loss of £25,000 while our nearest rivals H. Williams chalked up profits of £350,000.*

Control of the company was presumed to be in the hands of the managing director, my father and his father before him. This was far from the reality. Considerable dilution of the shareholding had taken place as generation followed generation. When I entered the business in 1956 our branch of the family, descendants of Willie, held just 39 per cent of the 11,000 ordinary shares. The descendants of his elder brother Adam, who were now living in England, held 37 per cent. We had little contact with that branch of the family. Maxwell, son of Herbert who died in Gallipoli, held 9.4 per cent and was a housemaster in Pangbourne Nautical College; my godmother Helen, the only daughter of Dr

* H. Williams collapsed in the early 1980s as a result of severe price competition. Its managing director, John Quinn, claimed to be the only other ‘certificated grocer’ in Ireland apart from Dermot.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

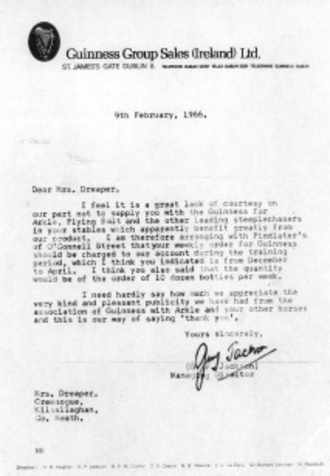

Arkle’s success was based on a daily dose of Findlater’s Guinness! Letter on display in An Poitín Stil, Rathcoole. Humans were also often prescribed stout, a snipe a day (⅓rd pint bottle) as a pick-me-up.

Alex, held 5.5 per cent. The problem of control was compounded in that the 66,000 preference shares had one vote for every ten shares held. Thus 8,800 votes were required for 50 per cent control. Calculations in 1958 showed that our branch had 8,518 votes before enlisting the support of Max and Helen.

On his death my father left everything, including his Findlater shares, to my mother. That’s as it should have been. His father had acted similarly in 1941 when he left almost all his shares to his daughters, my maiden aunts, Doris and Sheila. At the time Dermot was a bit put out by this— having as he saw it all the responsibility as managing director but not the shares

to support the position—but there was wisdom in Willie’s ways. In fact the first time control became an issue was in the aftermath of my father’s death. One of my first tasks was to secure control of the company for the Dublin branch of the family, Mother, Doris, Sheila and myself, with my godmother’s shares and a few small purchases. With 51 per cent pooled we were then in a position to deal with predators on our own terms.

Findlaters Corner, at the top of O’Connell Street, covered 26,000 square feet. The complex was our albatross. It was one of very few buildings in Upper O’Connell Street that had been largely undamaged between 1916 and 1922; it was old and needed rebuilding. It was producing good revenues but the costs were excessive. Discussions on its redevelopment were continuous from 1964. Management consultants were taken on in the autumn of 1966. Early in 1967 they presented detailed reports covering every aspect of the business. They endorsed the sale of Findlaters Corner, recommended the cessation of the beer bottling and whiskey bonding and, most radically, recommended the creation of a new kind of home delivery service in the form of a closed-door supermarket in south county Dublin. The plan was to transfer the delivery business from ten of our southside branches into one central location, paying an industrial rather

FINDLATERS

than a high-street rent, and operating a streamlined telesales and picking system.

The board gave the plan the green light. This was our last chance. There was no room for error. It had to be a success. We were transferring some £400,000 [€7.3m] worth of sales from the shops to the new operation. It would break even at half that level. Prices could be as competitive as the supermarkets. The customer was to receive a super service and the branches would be free for conversion to self service. The firm became a hive of activity. The plans were innovative and exciting. The ball had to bounce in our favour. The phased conversion of ten branches to self service, using the experienced Sainsburys’ shop fitters, was approved.*

Savings needed to be effective in every corner of the business, and if the survival plan was to work, we needed the staff to be behind it, despite the fact that jobs were going to be lost. I called the staff to a meeting in Liberty Hall, gave them the facts on the conversion of our shops to self-service and the details of the rationalisation plans. The consequences of success and failure were clear. The meeting was receptive, and the general attitude positive, despite a natural fear of change. Staff numbers were reduced by one-third, from 341 to 227, with £70,000 being knocked off the wages bill [over €1.27m]. Transport costs were cut by £10,000 [€183,000]. Stock levels were scrutinised and surplus sold off to free up capital, mainly whiskey and claret. The beer bottling unit was closed down and the plant sold off in an effort to recoup book value.

The fact that Findlaters was faltering was not a secret, and predators were circling the camp. Inquiries for the company came fast and furious: in August 1961 from Louis Elliman for the properties, in November 1961 from Urney’s Chocolates, presumably to diversify, and in February 1962 from our long term competitors, Liptons.†

Dermot sent back a last spirited reply: ‘Dear Sir, We thank you for your letter of 26th February 1962. We did give, to my recollection, consideration to an offer for our firm from Messrs. Lipton’s in the year 1927, but on that occasion Messrs. Lipton’s had not the necessary cash which we wanted, namely, one million pounds. If Messrs. Lipton’s were to make us a stupendous offer, same would be considered by my Board, but I would state now that I personally do not think it is worthwhile pursuing the matter.’

Enquiries continued for the rest of the decade: in September 1962 from a law firm in Birmingham; May 1963 from a London broker; June 1964 from a London property company proposing sale and leaseback; May 1965 from D. E. Williams of Tullamore; July 1965 on behalf of Ben Dunne; November 1965 on behalf of Tesco. In 1966 Feargal Quinn called:

*Ronnie Nesbitt, MD of Arnotts, at that time urged me to be aware of the wisdom of gradualism.

† Liptons were founded by Thomas Lipton, who had Scottish parents and Irish grandparents. Born in 1850 he was knighted in 1898, and died in 1931. With over eight hundred stores in England, Scotland and Ireland they were one of the largest grocery chains in the early to mid twentieth century. Sir Thomas was a great sailor and philanthropist. In his enormous ‘Shamrock’ yachts he made five unsuccessful attempts to win the Americas Cup for Britain.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Labels from the 1960s

The 1960s range of wine labels which won an award of merit from the Irish Packaging Institute. Designed by Thalmadge Drummond and Partners of London who also created the Odlum owl design flour packs and redesigned the Jacob’s Cream Cracker packets.

FINDLATERS

I remember plucking up the courage to call and see Alex with the suggestion that maybe there was a future for us to work together. It was 1966 and I was in Finglas at the time and could see we had a profitable business formula but no money for new sites. It appeared to me at the time that the Findlater sites were underused. I had no fixed idea how we could work together but I remember going down and into those lovely hallowed wood panelled walls of O’Connell Street. I was shown to the fine office that Alex had. It was there that Alex broke the news to me that Findlaters were going into the supermarket business. ‘We’ve sat back long enough,’ he explained and told me of the decision to change from the traditional grocery methods to the new self-service concept. Those were very exciting years when change was sweeping through the trade. It was only then that we all began to realise that it was far easier to start from scratch than to create change in an existing business, with its established habits of management, employees and customers.

Feargal’s last sentence was so true. Liptons, Pay-and-Take, Monument Creamery, Bacon Shops, Maypoles, Leverett & Frye and most of the traditional retailers worldwide failed to make the transition.

In parallel to these straightforward approaches there was another more circuitous approach. In December 1964 Garfield Weston, owner of Associated British Foods and Fine Fare Supermarkets in the UK and over 150 companies in Canada and North America, had tumbled to the fact that there were living in England ordinary Findlater shareholders who had lost contact with the present generation in Dublin. He was an old and experienced hand at the game. He offered £10 per share, increased it to £20 and probably settled a little higher after a Dutch auction. This gave him 19.5 per cent of the voting stock, a shareholding that hung over our heads. Rumours of Weston’s holdings were published in The Irish Times. Three other shareholders were attracted by the new price but agreed to sell to us in Dublin. These shares were sold to our friends in Jacobs who saw Weston, with his biscuits and stores, as a potential threat, and so were glad to be on our side. They now had an 18.4 per cent holding, an investment which more than doubled in value as events unfolded. The family holdings were immediately rearranged into one controlling unit so that we were in the driving seat. Jeffrey Jenkins, chairman of Irish Biscuits (Jacobs), joined the board of directors.

At this delicate stage, we needed setbacks like a hole in the head. But they came, hard and fast. Harveys’ profits faltered, weighed down by an import surcharge and tax increases in the UK, and they were taken-over by unpretentious UK cider and Babycham giant, Showerings, whose performance on the stock exchange had been impeccable. Apologetically, and full of praise at our performance, Showerings moved the Harveys agency to their own under-performing company in Clonmel (Bulmers). This was a big blow. The compensation did nothing for the long term.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

there, and orders came pouring in: more than we could handle even with a smart new fleet of vans, with special wheel-in racks for the orders. We were perhaps foolish to open so close to Christmas. We made lots of mistakes. We fell short on performance measurements at all levels—telephone response, picking and deliveries. The weather was foul, and the service got off to a

New livery for the home delivery service 1967

terrible start. The vans were too wide to fit through the average household gate—and those lovely clip-in delivery racks would not wheel on gravel! Elementary. Common sense is sometimes a scarce and valuable resource. I sadly ended the service after three months. There was, however, a consolation prize: by closing the home delivery service, the branches had been cleared of a lot of costs.

While all this was going on, the usual company routine of people joining and people retiring provided a reassuring atmosphere of normality and continuity. The men and women who had been the backbone of Findlater’s service were given appropriate send-offs.

In August 1967 a reception was held in honour of Richard Haughton (seventy-one), grocery manager in Dún Laoghaire, and Francis P. O’Flynn (seventy- five), general grocery traveller who both retired from the company in that year. Frank was born in Collon, Co. Limerick. He worked with the Home and Colonial Stores from 1914 until he joined Findlaters in 1931, with the exception of two years spent in Flanders with the British Army Medical Corps during the First World War. He represented Findlaters to hospitals, hotels, restaurants and institutions. Richard Haughton retired with 56 years’ service; he joined the Kingstown branch in 1911. In 1915 he was given leave of absence to join the British Army fighting in France; he rejoined the firm in 1919, and refused promotion to stay in the Dún Laoghaire branch until his retirement.

In November 1967 the house journal, the Findlater Herald announced to its readers that

More than 300 years—that is the almost unbelievable total of service which seven Findlater employees who retired recently gave to the firm, bringing to almost 2,000 the number of years of cumulative service to Dublin shoppers by our 52 pensioners. And it is a measure of their own spirit as well as the company’s regard for them that these seven have contributed over 40 years to the success story of Findlaters. Among the more recent retirements is that of Mr Joseph Hayes, much-respected manager of our Blackrock branch, who spent in all 48 years with Findlaters. Mr Ignatius Butler, who has retired as manager of the Sandymount branch, gave the company 41 years of service. Known to his colleagues as an extremely hard worker, he held in all three managerships, the others being at George’s Street and at Baggot Street. His service has been

FINDLATERS

1960s shop posters

The proposed shop front for the planned supermarket in Dun Laoghaire

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Findlater Herald. November 1967

much appreciated by staff and customers alike.

By way of contrast, Miss Mary McLoughlin, who leaves as office chargehand in Blackrock after 48 years, has been at that branch during her entire career. She was very popular with many local shoppers, having known many of them since they were toddlers.

Also well known was Miss Lilian Furlong, who leaves the fruit and vegetable department in Dalkey after more than 40 years of excellent work. Her counterpart in Rathmines, Miss Mary O’Toole, was renowned for her great enthusiasm for work, and has been described by at least one of her fellow-workers as one who was ‘always rushing about the place’. Miss M. Dowling leaves the Dalkey branch, where she was employed as office chargehand, after 44 years at Findlaters. Miss Ethel Lea, who devoted so much work to the confectionery department in Sandymount, has been with us for 42 years, some of which she spent at Baggot Street.

Early in 1968, notwithstanding the improving ratios and an upward sales graph, all the exceptional and unexpected items outweighed the good work, and I decided to consult with the fledgling and thrusting Investment Bank of Ireland before we haemorrhaged further. There were only two merchant banks in Dublin at the time, the other being the venerable and long established Guinness & Mahon, then managed by the founding families. We were now looking for someone to buy us, but during the course of the next six months all the recognised suitors fell by the wayside. These included Le Riches stores in Jersey and H. Williams. Jack Cohen of Tesco was most courteous and tried to persuade me to take up a job with them. I protested that I was in his office to give him an

FINDLATERS

opportunity to enter the Irish market. We even called on Jack Musgrave* in Cork but were ahead of our time. Garfield Weston’s son Galen initially said ‘No, thank you’. So I bought back his shares. Then finally he said Yes, he would do a deal. He would take over Findlaters with its tax losses, ex gratia pensioners, six of our branches and as many licences as would transfer. The assets that he did not want were to be moved into a parallel company. These included the O’Connell Street property, the St Lawrence Hotel and public house in Howth with the filling station attached, the wine division, and some fourteen branch shops.

I shall never again see the sight of a slim lone thirty-one-year-old man of impeccable presence carry so gallantly such a burden, no more than I shall ever again see a handsome, twenty-eight-year-old [Galen Weston] accept and lift that burden, in the Gresham yesterday afternoon, behind the closed doors of the ballroom. The young Alex Findlater spoke with grey haired gravity to the combined staffs of all his branches, to tell them that it was all over and that Findlaters, as Dublin knew it, was finished.

In a silence so loud that I could hear it through the closed door, he announced the various degrees of taking care. Every one of the Findlaters’ staff are being taken care of financially. There is a redundancy of some 175 people, but each and every one of the one-time Findlater staff have provision made for them. As befits a family business with a great and honourable tradition.

The Findlater name survives as a wine and spirit merchants. It would seem that as far as possible everyone has been taken care of . . . the Findlater staffs, the Shareholders (a small, modest and undemanding group), and in the heel of the hunt there emerges the Findlater honour.

Eventually we sold our premises in O’Connell Street and Cathal Brugha Street to Ronald Lyon for property redevelopment; the St Lawrence Hotel to wine merchant, Bill Campbell. The branch shops not taken over by Galen Weston were sold individually, mainly at auction through Lisneys. With some difficulty plant and machinery, fixtures and fittings were sold for at least book value by a phased and diligent disposal within the trade over the course of a year. Wine stocks surplus to the requirements of the continuing wine division were snapped up by the trade and wine enthusiasts. The shareholders fared well. The whole wind-down and asset disposal was handled by myself and John McGrail, assisted by the able team in solicitors A. & L. Goodbody, and by the company secretaries Kinnear & Co.

Having sold the headquarters, the question was—what next? I told Louis O’Sullivan, editor of Checkout, in an interview published in February 1969:

* The Musgrave Group, which incorporates 165 family-owned Super Valu outlets and 270 Centras, now controls an amazing 22 per cent of the country’s grocery market.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

The author and Galen Weston in the Gresham Hotel. 30 December 1968. (Photo: Independent Newspapers)

When we sold the O’Connell Street premises for £353,000 [2013 = €6.2m] for 26,000 square feet] we had to make the decision whether the money should be reinvested in retailing (we had plans ready to develop our major shops in Dún Laoghaire, Foxrock and Rathmines) or in other fields. Naturally our first preference was the field we knew—retailing. However we took the best financial advice available and found it impossible to recommend that this money should be put back into the grocery trade. The ten shops we had converted were only on average breaking even. We had to look at the environment of the whole market and the future funds that would be needed to remain one of the horses in the race. Maybe we didn’t move far enough, fast enough, but we did get to a point where we felt the temperature of the market and decided that it was too hot!

In such an enormous old place as the O’Connell Street head office, with many activities up and down stairs, in cellars and lofts, and an incredible variety of goods flowing continually through, it was perhaps inevitable that ‘leakage’ should occur. After we closed in 1969, ex-staff used to say sympathetically: ‘I’m sorry Master Alex, you’se was robbed!’ implying that there was more slipping out of the place undocumented than we detected, and we did have some big detections. The archive has many

Selfservice and Supermarket December 1968

sad records, such as the letter from the Sandymount branch manager to Adam explaining how provision man O’Rourke had been caught stealing a ham just before Christmas 1899; or the barmaid sacked

FINDLATERS

Ronald Lyon’s proposed redevelopment of Findlater’s Corner

from the theatre in 1900 for irregularities in the stock, and in 1930 the husband and wife team working scams in the gallery and pits bar, and in 1934 when 25½ bottles of spirits and 49 bottles of wine were found filled with water in the cellar, and the cellarman had to go.

On one occasion I saw a man loading a large amount of drink outside the O’Connell Street warehouse. Full of enthusiasm, I dashed up to give the customer a helping hand—later learning that I had contributed to a heist, which was being carefully watched by management! On another occasion there were inexplicable shortages in the provision department in Thomas Street. This store did a good trade in baby Powers and snipes of stout, but also in bacon. Eventually a plant was put in, in the form of a private investigator in Findlater shop attire, supposedly transferred from another branch. After the announcement of a surprise stock-take the investigator decided that he would not go out for lunch when the shop closed for the hour. To his surprise several sides of bacon walked into the closed shop from Liptons up the road. The stock-takers duly arrived back and confirmed that the stock count was correct, and the bacon then returned to Liptons after they had gone. Unfortunately, the management plant had seen all, and the secret was uncovered. Such are the vagaries of trade!

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

My sister Suzanne and Frode Dahl who married in Findlater’s Church 17 May 1969 seen outside the church on the way to a friend’s wedding.

tered post £200 in part settlement of goods received from your shop while in O’Connell Street. I now enclose the balance of £300 to fully settle the account. Once again I apologise for my slowness in paying account; better late than never. It has been worrying me for some time.’ (In current terms, this writer was owning up to stealing some £5,500 worth of goods from the company.)

It had been our intention to set up our wine division independently. However, without premises, a merger with FitzGeralds, the wholesale tea, wine and spirit merchants, which had extensive premises in Westmoreland Street, was a more attractive option. This highly respected company had been established in 1861 by Martin FitzGerald (1864-1927), born in County Mayo, who was the proprietor of the Freeman’s Journal (1919-24) and an intermediary between Michael Collins and Sir Alfred Cope, the British assistant under-secretary for Ireland 1920-2, in the negotiations leading to the Anglo-Irish truce in July 1921. Martin was a keen follower of horse-racing as was the celebrated Nora FitzGerald who passed the company on to her nephew and niece, Jim and Catherine FitzGerald. They were the agents for Haig Scotch whisky, then one of the biggest selling brands, Bisquit cognac, another good seller, and other important brands of wines and spirits. I was a non-executive director of the new company which traded as FitzGerald Findlater & Co. Ltd.

After a year selling stock and equipment in our O’Connell Street premises, I departed on a peregrination around the language schools of Germany, Switzerland and Spain, culminating in Insead, the international business school in Fontainebleu. While on this peregrination FitzGerald Findlater were taken over by Edward Dillon & Co. Ltd, distributors for Hennessy, Gordons, Sandeman, Lanson and other leading brands. My first move when back in

FINDLATERS

Dublin was to buy back the rights over the Findlater name in the wine trade by purchasing Findlater (Wine Merchants) from Nigel Beamish, managing director of Edward Dillon & Co. Ltd.* This set the scene for a return to the trade. One of the conditions of the sale of Alex. Findlater & Co. Ltd. to Galen Weston had been that I was forbidden from re-entering the grocery trade under my own name, but the restriction in the wine trade lasted for only three years.

After the Insead course I was still in my thirties, but quite unsure where my future lay. I attended a vocational guidance clinic in Harley Street, London in order to find out what my true vocation was. I was convinced that I should be leading safaris across the Sahara and in Latin America. I was fit, sporting and had a good command of languages. Rather disappointingly they pointed me back to my home base and the trades I had been brought up in and assessed that I was better at selling a service than a product. On reflection, that is much of what my role in Findlaters was all about.

But I had found a new confidence after Insead and, setting aside the advice gained in Harley Street, was receptive when the idea of theatrical promotion came up. With two much more resourceful friends the plan was to promote Sammy Davis Junior for a week in the Grosvenor House, London. The success of this was followed by a week of Marlene Dietrich in the same venue. Unfortunately, this time we learnt that the downside of theatrical promotion can be pretty painful. However, there’s always a next time and some years later, in 1986, with some of the same friends, I was involved in the first full staging of the Bolshoi Ballet in Dublin. For the four performances a 4,000 seat theatre had been constructed within the Simmonscourt extension of the RDS. Such was the ‘occasion’ that many of the guests attended the opening performance in full evening dress. The reception was pulsating. The press headlines read: A BOLSHOI BALLET EXTRAVAGANZA!, FROM RUSSIA WITH GRACE, IVAN THE ATHLETE AND A PORTRAIT OF BOLSHOI BEAUTY. This was one of the first events at which ‘corporate hospitality’ had been offered with champagne before the show and dinner afterwards, in a purpose-built dining room on location. A truly memorable occasion.

New Findlaters

Our next step was to relaunch Findlaters as a wine merchant in its own right. Having examined a variety of options and locations we acquired a retail premises in Upper Rathmines, a suburb of Dublin. This time we clearly identified that we were to be wine merchants exclusively, the financial resources required to support spirit agencies being beyond us.† We re-entered at the tail-end of a slump in wine prices and could offer great value to our private clients. And so

* Dillons were, in turn, taken over and have had a variety of industry shareholders and remain to this day, a force in the Irish wine and spirit trade.

† Just as Alexander Findlater the founder moved into whiskey in the 1820 ahead of a boom in spirits, and then built a brewery in 1852 to benefit from the switch from spirit drinking to beer, history shows that we chose correctly. The Irish wine market has risen from some 800 cases a year in 1974 to over 4 million a year in 2000, and is still growing.

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

the business grew, offering good value and a lot of service. We bought freely on the market and one by one restaurants came to us for supplies. This was the encouragement we needed. Trade expanded and old suppliers reappeared, some who had had a lean time in Ireland since the changes to old Findlaters.

Shortly after we opened in Upper Rathmines in 1974 and were tight for money, a large car drew up at the door. The gentleman tendered a £100 note for a small purchase, an enormous sum at the time. We apologised profusely that we did not have sufficient change. He was not at all perturbed and left it in our safe hands. This was Joe Murphy, founder of Tayto Crisps. He was reciprocating a good turn. In the early days of Tayto, when he was in dire financial straits, he called on Dermot and offered him half of his company or more, then based in a small premises off Moore Street. He was on his knees. ‘No’, said

Dermot, ‘keep your company’—and he came up with a plan. He would promote Tayto in all Findlater outlets, get his commercial travellers to promote them to the trade, pay the account in seven days and more importantly, Joe’s wife could buy her groceries on ‘tick’ in Findlaters’ Malahide branch until the position was under control; six months or more, whatever was necessary, and then repay little by little as the cash flows permitted. It was a lifeline to Joe. He was relieved, Tayto became brand leader and Joe’s thank-you was in turn much appreciated by us. Eventually Tayto was taken over by the American multinational, T. C. L. Beatrice Foods, in 1964 and, then in 1999, bought by Irish based international drinks group Cantrell & Cochrane, for £68 million.

Trade in the 1970s and 1980s was not an easy ride. We were constantly short of funds and seeking family support. Personal guarantees ensured that we paid ourselves modestly and put off the funding of pensions. Profits were ploughed back and by degrees the business strengthened. This was the time I did my service behind the counter, an activity denied me when I entered old Findlaters many years earlier. Slowly, we created an atmosphere in Rathmines which our customers liked. We were competing for much of our trade with Mitchells of Kildare Street, a fine old wine merchant with excellent agencies in Krug, Remy Martin, Famous Grouse, Deinhard, and other good brands. Thoughts of a

FINDLATERS

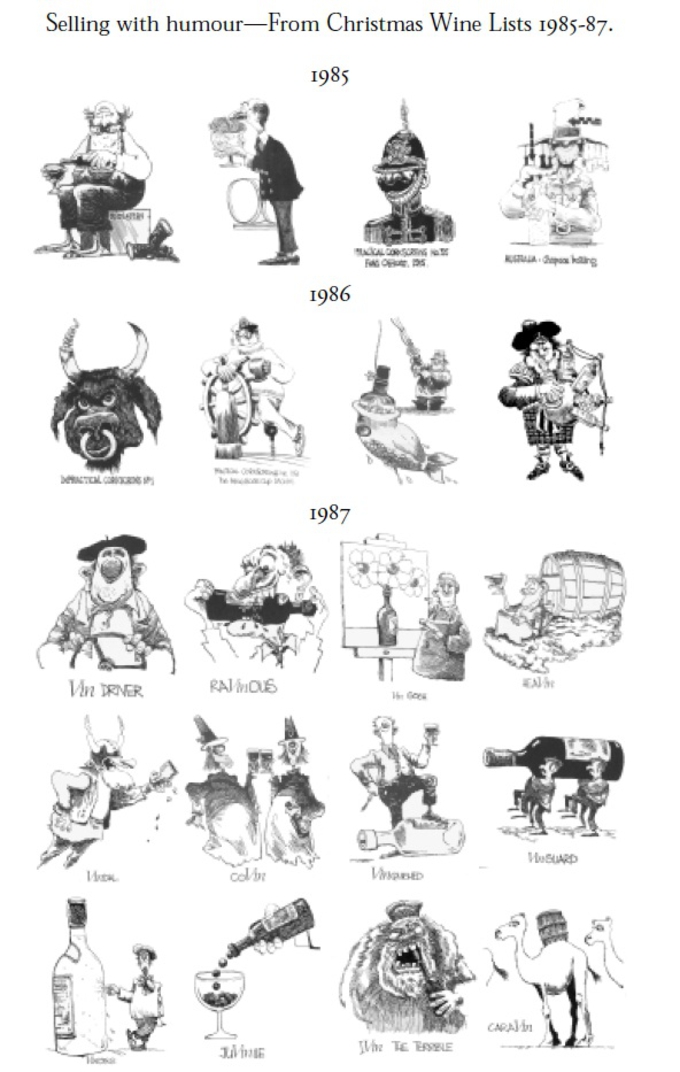

Illustrations by Martyn Turner

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Our lists in this

period were designed to entertain and give

knowledge. Other excellent lists were

illustrated by Harry McConville (1977 &

1988), Veronica Haywood (1979), and John Donohue

(1980). Martyn Turner also illustrated 1981,

Tony Colley 1982 and Uto Hogerzeil 1983 &

1984.

FINDLATERS

merger were explored from time to time, but to no avail.

By the early 1980s trade was going ahead in leaps and bounds but space was our major concern. We began to expand, buying the property to our right and behind us in Rathmines, but by the mid-1980s were again short of space. As an associated activity we had developed part of the area into the Wine Épergne Restaurant, created and managed first by my former partner Seong and then by Kevin and Muriel Thornton, who are now enjoying considerable success in Portobello with two Michelin stars.

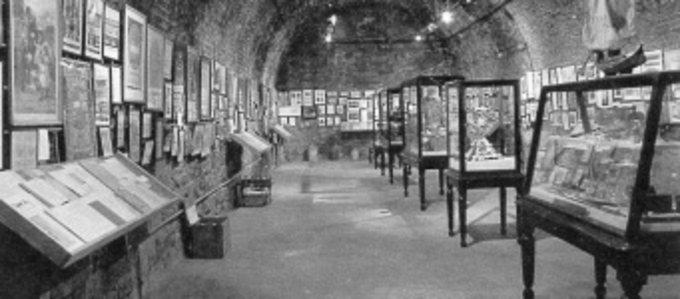

Mark Kavanagh of Hardwicke, whose father, with great foresight, had bought the whole property block from CIE when the railway closed in 1953, let us inspect the property. It was derelict. The walls and ceilings were grimy from years of seepage from the station above. The area had been used previously by Gilbeys as a bonded warehouse for maturing casked whiskey but they had surrendered their lease when the bonding of whiskey was taken over by Irish Distillers. The floors were, on the whole, of good sterile soil. The lighting was non-existent and the headroom between many vaults only four feet high. With heavy hearts we were about to walk away from the idea when Morrough Kavanagh suggested we consult an engineer. Christopher Pringle from Monaghan looked, paced, measured, shook his torch for more light, stubbed out yet another cheroot and said, ‘Well, it could be done—at a price.’

The plan was simple—let’s not call it a ‘business plan’ as taught at Insead—it was to press ahead with the development when we got title, and sell our Rathmines premises to fund the refurbishment, any shortfall to be covered by increased borrowings or by recourse to an investor. We opened in 1991 with six of the twenty-one vaults floored. We invited professional and business friends. Nick Robinson, Chairman of the Irish Architectural Archive performed the opening ceremony. Few gave us much chance of survival but they were polite and did not say it! We had not bargained on a depression and sky-high interest

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

Senior citizens at the opening of the Vaults. (left to right) My mother Dorothea, Stanley Fleetwood (retired manager), my aunt Sheila and Ned Kelly, who used to service the Trojan vans. (Ned passed away on 16 July 2001) (Picture: Photostyle)

rates in our first year. However, we only recorded one small trading loss and thereafter the graph climbed upwards. We were under pressure to bring in investors to reduce borrowings and fund the renovations to the other fourteen vaults. A detailed plan was written and three most suitable investors found.

Some credited us as with ‘lateral thinking’, moving into the city centre when others in the trade were moving out. Certainly, the location brought us into close proximity with the many city eating establishments which enabled us to give them a top class service. The splendour of the vaults and the presence of the museum, recording pictorially the story of our activities as merchants in Dublin over the past 175 years, coupled with a top class selection of wines, helped us to restore the company’s public profile. As Philip Smith and Peter Leach in The Family Business in Ireland put it when discussing entrepreneurial characteristics: ‘The need to achieve personal goals is central to their characters, and personal satisfaction (i.e. building a successful business) is usually a stronger motivating force than financial reward’. Times were tough but we doggedly won through.

Now the company is in outstandingly good health and a leader in its industry. Since the move to the vaults we are selling over seven times more wine and our market share has increased fourfold. Unusually for a private company of our size we have a strong board with two non-executive directors, Lochlann Quinn, chairman of Allied Irish Banks and deputy-chairman of Glen Dimplex, the world leader in electrical consumer products, and Brian Smith, until his recent retirement, a director of Beck Smith and Batchelors Ltd, part of Northern Foods, one of the UK’s leading plcs.

It is recorded in Chapter 2 that my great ancestor ‘exhibited a wonderful ability—indeed almost an intuitive power–in the selection of his employees,

FINDLATERS

The Excise office outside the vaults prior to our restoration.

The back vaults beyond the museum.

The main area, one of 8 vaults this size (c.360 sq metres each)

Museum, one of 10 vaults this size (c.110 sq.metres.each, the others being used for document storage) The Vaults are numbered 1 to 22 (but there is no number 12) and cover the area of some 48,000 square feet

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

147-149 Upper Rathmines Road (Watercolour by Pat Liddy)

many of whom, as time passed on, became his partners.’ And so it has been in modern Findlaters. Most business teaching advises against joint managing directors. It has worked well for us with Frode Dahl, my brother-in-law, in control of finance, warehousing and administration and Keith MacCarthy-Morrogh in charge of sales and marketing. Frode navigated the company through the choppy waters after our move to the vaults, found alternative sources of income when funds were needed, saw to improving performance ratios and, most importantly, protected margins against competitive pressures. It’s a busy fool who builds volume at the expense of margin and reports profits unchanged.

Keith, who was invited to join us in 1993, had spent the previous twenty years with David Dand and Tom Keaveney building up Gilbeys of Ireland to the No. 1 position in the Irish wine and spirit trade and establishing Baileys as the largest

Frode Dahl, Knight 1st Class, Royal Norwegian Order of Merit, being presented with the honour by H.E. the Norwegian Ambassador, Kirsten Ohn, 30th November 1990.

selling cream liqueur world-wide. He came to us with a wealth of experience and enviable contacts. He repositioned the company as distributor of quality wines from renowned independent producers, giving us some of the world’s best loved wine names, a policy that has proved an outstanding success.

Quality has been the bedrock of the Findlater business since its inception. Nigel Werner, who joined Frode and myself from the start in 1974, is the present custodian of our enviable rep-

FINDLATERS

utation for quality. He maintains a close working relationship with our specialist producers the world over. It is a job that requires an acutely sensitive nose and palate, a good memory of tastes, flavours and aromas and a recall of the characteristics of grape varieties, vineyards and vintages that make up the galaxy of wines available on the world market. All this must be coupled with a thorough knowledge of our market so that our lists have a good balance for all palates and pockets. Nigel also champions another important area where the buying of wine has changed since Dermot’s days. Then we bought, cellared and matured on our own account. The carrying cost and uncertainty of this caused the downfall of many reputable English wine merchants. Now we market the top Bordeaux and Burgundy growths under a system known as ‘en primeur’ where the client is given the opportunity to invest in the maturing stock for his or her future pleasure, or perhaps for speculative gain.

‘Wine-speak’, the use of elaborate and flowery metaphors to describe the aromas and palates, has often left the aspiring purchaser no wiser as to what the choice should be. There is no better champion of easy to understand advice on the merits of all our wonderful wines than David Millar, whose joy it is to impart his knowledge to as wide an audience as possible. He, Barry Geoghegan, recently appointed sales director and Richard Verling, associate director (restaurants) are in the forefront of the sales team. All came to the company with a bundle of experience in the industry and have excellent wine knowledge and exceptional talents in their chosen areas of responsibility. They are part of the management team that has refocused us in the past and will do so again in the future. Findlaters is a happy company with a strong collegiate spirit.

This is the firm that I have led since 1974. Its success has been beyond all our expectations. In the last decade we consistently out-performed our annual business plan. There is no doubt the booming Irish economy has helped us along. But it needed, and we had, an exceptional team to capitalise on the opportunities. We also had our strokes of luck. We were rewarded for restoring the vaults as an historic building. This gave us an important tax break when we most needed it. By 1996 our finances were in good order, borrowings were almost eliminated, personal guarantees were removed, profitability was rising and dividends were beginning to flow.

The time was now right to relinquish some of my executive responsibilities. As Smith and Leach put it: ‘Most entrepreneurs love the excitement and the challenge of this pioneering phase. . . ‘ Thus in January 1997 Frode and Keith took over as joint managing directors. For the first nine months I remained as executive chairman and started the research into this book. Smith and Leach continue: ‘Succession should not be an event. Ideally, the owner’s transition from MD to chairman is so gradual as to be imperceptible. Successors grow into their roles, earning the respect and confidence of the owner, and the owner gradually becomes accustomed to a new role.’ In late 1997 I changed my role to non-executive chairman and full time researcher and scribe.

As we leave the year 2000 a new chapter in the history of the company is about

FROM OLD FINDLATERS TO NEW

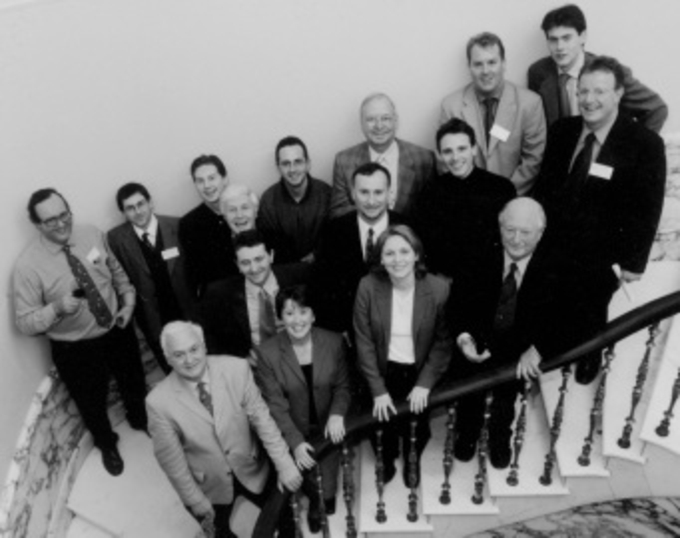

The Findlater Team

at the company’s annual trade Wine Odyssey

February 2001.

Back row: Anthony Tindal, Werner Hillebrand,

Dan Gregory, David Millar, Michael Williams,

Tom Mullet, Barry Geoghegan, Matt Tindal.

Middle row: Karl O’Flanagan, Nigel

Werner, David Geary, Richard Verling.

Front row: Keith MacCarthy-Morrogh,

Maureen O’Hara, Aisling Norton and Alex.

Absent: Managing the vaults and

keeping the show on the road: Frode Dahl,

John McCormack,

Brian McCollum, Damien Archer, Frank

Donohoe, Marc Meehan, Sarah Malone, Anne

Gahan,

Juliet Brennan, Sarah Grubb, Genevieve

McCarthy, Nicola Healy, Richard Nash and his

merry

team from Munster, and the hardworking bond

and dispatch team. (Photo: John Geary)

to unfold. The industry is changing. Demand for wine is growing across the world. New vineyards are being planted, knowledgeable winemakers teamed with marketing people are replacing the gentlemenly winemen of yesteryear. The physical quality of the wine is now much less variable than it was in the past. They say that globalisation is taking over but there are still an enormous number of really good producers in private hands, who run excellent businesses and need distributors such as ours. We ourselves are on the threshold of a move from the Harcourt Street Vaults to a new purpose-built bonded warehouse and distribution centre in the west of the city, a project that will enable us to double the size of the company within the next five years.

Over its long and wonderful life the story of Findlaters has been about the family that owns the company, the producers who supply the goods, the executives who manage the business, the staff who serve the customers, and, not least, the loyal customers who support the whole. Smith and Leach put our advantage in perspective:

FINDLATERS

Culinary entrepreneur Darina Allen, Winner of the 2001 Veuve Clicquot Business Woman of the Year award, with Keith MacCarthy-Morrogh, joint managing director of Findlaters. Alexander, the founder, no doubt knew Madame Clicquot, advertising Champagne bought from her in her lifetime in The Irish Times on 26 December 1861, priced at 78s a dozen. (Photo: Kierán Hartnett).

Commitment and a stable culture lie behind the fact that family businesses are generally very solid and reliable structures—and are perceived as such in the market place. Many customers prefer doing business with a firm which has been established for a long time, and they will have tended to build up relationships with a management and staff. Also, the commitment within the family business . . . reveals itself to customers all the time in the form of a friendlier, more knowledgeable, more skilful and generally much higher standard of service and customer care.

Addendum.

At the height of our success, in

2001, we were taken over by

Cantrell & Cochrane.

Findlaters is now trading

successfully as the Findlater Wine

and Spirit Group, part of Robert

Roberts Ltd, another old Dublin

trading name in the coffee trade,

both subsidiaries of quoted DCC.

When C&C took us over they

owned Bulmers Cider, C&C

International (Tullamore Dew

whiskey), Irish Mist Liqueur and

Carolan's Coffee Liqueur). Also

Ballygowan water and the C&C

soft drinks, Club Orange etc. In

September 2008 DCC bought the

business from C&C. In 2009 the

other long established wine firms,

Grants of Ireland and Woodford

Bourne of Cork were merged to form

The Findlater Wine and Spirit

Group, wholesaling through the

country. And so the great legacy

continues.

Notes and references

- Both papers March 1962

- Philip Smith and Peter Leach The Family Business in Ireland Dublin: Blackwater Press and BDO Simpson Xavier 1993 p 38 Sir John Harvey-Jones in the foreword to Philip Smith and Peter Leach’s excellent book The Family Business in Ireland said ‘Family businesses comprise over 90 per cent of all the businesses in Ireland and it has been estimated that over 50 per cent of people employed are employed in family businesses’. Findlaters are proud to be amongst their ranks